Libertyville has been home to many Lake County firsts, but did you know it was the first county seat? Through a series of events, including but not limited to surreptitious petitioning and a rather bitter political feud, Libertyville went from a small but upcoming village to county seat, then back to a village.

Arriving in 1835, George Vardin and his family were some of the first non-native people to live in what would become Libertyville. They built a small, one-room log cabin on the south side of a grove of large oak trees near what today is the site of the Cook Memorial Public Library [1]. While they didn’t stay long, moving further west sometime within a year, their cabin became the home of another pioneer, Henry B. Steele. Other settlers joined him, calling their small settlement Vardin’s Grove. The village grew quickly, changing its name to Independence Grove (1836) and then to Libertyville (1837). It boasted the areas first schoolhouse, blacksmith, and medical doctor. On April 16, 1837, Henry Steele was appointed postmaster for one of the area’s first post offices, which he ran out of Vardin’s cabin [2]. He was succeeded as postmaster by Horace Butler in 1843 who, like Steele, used his home as a post office during his term as postmaster for the village.

Horace Butler’s cabin. Date Unknown. Photo courtesy of the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

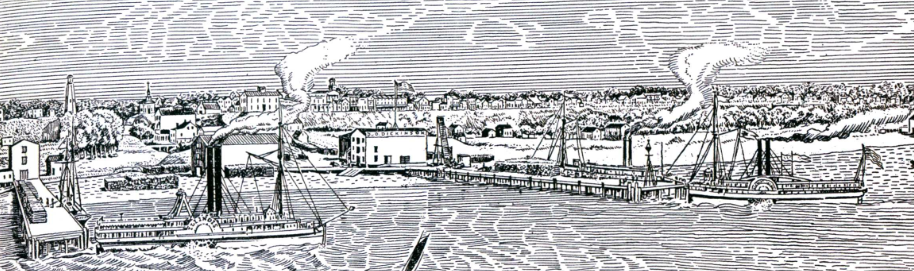

The village of Little Fort (known today as Waukegan) was developing just a few miles away. While a small trading post had been established by fur traders sometime between the 1720’s-1790’s (there’s disagreement about the exact date), it wasn’t until 1835, when ownership of the land was transferred by treaty from the Potawatomi to the United States government, that settlers came in any real numbers [3]. One of the first to arrive in the area was Thomas Jenkins. Originally from Chicago, he built a two-story frame store on the site of the former trading post [4]. Situated on Lake Michigan, the village was ideal as a hub for transporting goods. However, despite the construction of a saw-mill, furniture factory, and the arrival of the village’s first doctor in 1838, the settlement’s growth soon stalled. No additional frame buildings were erected until 1841. According to Elijah Haines’ Historical and Statistical Sketches of Lake County, State of Illinois most residents lived in one of the two or three one-room log cabins or in tents along the lakefront [5].

Little Fort, 1847. Photo courtesy of the Waukegan Historical Society.

At the time, both villages were part of McHenry County, comprised of what is today McHenry and Lake County, with the county seat located in the city of McHenry. The bulk of the population was concentrated on the east bank of the Fox River (which at the time did not have a bridge), forcing residents to pay 25¢ ($7.08 today) to use a ferry every time they wanted to visit the county seat [6]. Residents quickly tired of having to hand their hard earned money over to the ferryman, and petitioned the State Legislature to divide the county. Their petition was granted and on March 1, 1839 the Illinois General Assembly passed an act which divided McHenry County, created Lake County and appointed commissioners to decide on the location for the new county seat [7].

On June 1, 1839 commissioners Edward Hunter and William Brown met at the home of Henry B. Steele in Libertyville to discuss possible locations. After some debate, they decided that Libertyville, which was geographically close to the center of population in the new county, would be the ideal location for the new county seat. The commissioners also renamed the village Burlington, the fourth name the village had had in the span of three years. Despite the new county’s limited funds, in January 1840 commissioners contracted with Burleigh Hunt, who had recently emigrated to Little Fort from Canada, to construct a two story courthouse on Division Street (West Maple Ave. today) that would be leased to the county for “a term of years” [9]. Once construction on the building had been completed, Hunt sold the building to Henry Steele for $500 ($15,614.71 today), who in turn leased it to the county. Even as the residents of Burlington were celebrating their newfound status, plans were quietly being put in place to move the county seat (and the political and economic power that came with it) to Little Fort.

Approximate location of the frame building housing the county courthouse. Libertyville Plat Map, 1885.

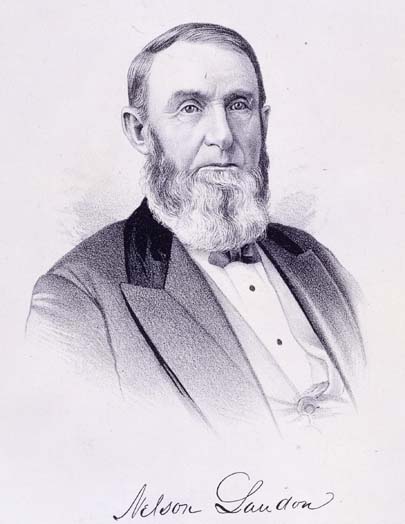

In August 1839, just two months after the formation of the new county, a group of prominent businessmen from Little Fort, including Thomas H. Payne, Lansing B. Nichols, and Nelson Landon, the largest land owner in the county, formed the Little Fort Party with the aim of getting the county seat relocated to Little Fort. Winning election to the county board of commissioners, Landon and his allies worked to delay the construction of the county courthouse in Burlington. The next year was a census year, and the group made sure that Capt. Morris Robinson, an ally of Landon, was appointed to take the count. While making his rounds, Robinson, said to have been a persuasive talker, presented people with a petition for the removal of the county seat to Little Fort, which led to “much hard feelings and ill will” among residents [10]. Once they had garnered enough signatures, Robinson traveled to Springfield (supposedly on foot due to the poor condition of the roads) to present the petition to the Legislature. He must have been quite persuasive since the legislature passed an act authorizing a referendum to be held on April 5, 1840 to determine the location of the County seat [11]. The boosters of Little Fort continued to lobby throughout the winter, while the people of Burlington, feeling sure of the outcome of the vote, did relatively little to put forth their case [12].

Nelson Landon. Illustration courtesy of the Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County.

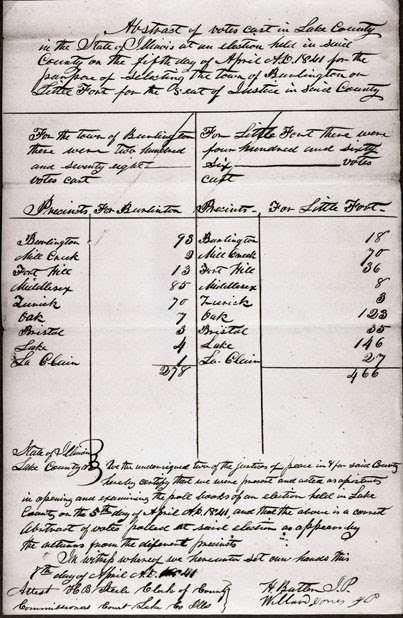

Tally taken for the vote to move the county seat from Burlington to Little Fort, April 5, 1841. Photo courtesy of the Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County.

The date of the election came, and to the shock of Burlington’s residents, the vote count was 560 in favor of moving the county seat and only 372 against [13]. The people of Burlington questioned how 200 more people had voted in the referendum than had voted in the 1840 election of county officials. Archimedes B. Wynkoop, a Burlington resident and the deputy county clerk, officially refuted the vote count, claiming that there were only 486 residents who could have voted and saying that “If everything had been conducted honestly, the county seat would have remained at Libertyville by a majority of 16.” [14] Accusing the Little Fort Party of “skulduggery” and of bringing in votes for-hire from Wisconsin, Will County and Chicago, the people of Burlington quickly formed the Grove Party with the aim of delaying the construction of county buildings in Little Fort and to try and prove that the vote had somehow been tampered with [15]. The efforts to prove fraud were hampered by the fact that the election records were moved to Little Fort on April 13, ostensibly as part of the changeover of the county seat. Steele and Wynkoop initially moved their offices to Little Fort along with the rest of the county officials before returning to Burlington in protest after Isaac R. Gavin, Clerk of the Circuit Court of Lake County, claimed that the removal of the county seat to Little Fort was not legal.

The feud between Steele, Wynkoop and the commissioners from Little Fort escalated until August 1841, when Commissioner Nelson Landon called a special court to dismiss Henry B. Steele from his duties. Landon charged Steele with negligence and incompetence due to his working from Libertyville, and was replaced by Arthur Patterson. The commissioners also fined Wynkoop $10 for contempt of court and $5 for repeating the offense ($156.15 today) [16]. In response, Steele and Wynkoop sued the commission in the circuit court. The court ruled that since Landon had not yet been sworn in as head of the Commissioner’s Court he had no authority to call the special term of the court. Steele was reinstated and Wynkoop’s fines were waived. While the Grove Party and Little Fort Party continued to feud, the issue of the location of the county seat was officially settled on January 19, 1843 when the Illinois Legislature declared that all acts of the special session of the commissioners were legal and binding [17].

Courthouse and Recorder’s Office (left) in Little Fort, 1870. Photo courtesy of the Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County.

The bitterness subsided over time and the first term of the Circuit Court was held at Little Fort on October 20, 1841. The first permanent county courthouse was completed by Benjamin P. Cahoon of Racine, Wisconsin in 1844. Built in a Doric style with classic columns, the courthouse cost $4,000 ($144,904.53 today) [18]. In March 1849 the village of Little Fort changed its name to Waukegan, the Potawatomi word for “fort” or “trading post” [19]. If you’d like to know more about the Lake County Courthouse, check out the excellent post about it on the blog of Diana Dretske, historian for the Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County, or stop by the local history section at Cook and check out the sources used in this post!

Sources

- Carroll, Charles Edward. Talk by C.E. Carroll, to a group of Methodist church women, on January 21, 1960.

- Boscarine, Leonard. Vardin’s Grove, Independence Grove, Burlington, Libertyville. Libertyville , IL: Libertyville Bicentennial Commission, 1976. Pg. 4.

- Link, Ed. Waukegan: A History. Waukegan, IL: Waukegan Historical Society, 2009. Pg. 11-12, 15-17, 131, 141.

- Halsey, John J. A History of Lake County, Illinois. Philadelphia, PA: R.S. Bates, 1912. Pg. 54-58, 62-71, 72-83.

- Haines, Elijah M. Historical and Statistical Sketches of Lake County, State of Illinois. Waukegan, IL: E. G. Howe, 1852. Pg. 20-35.

- History of McHenry County, Illinois: Together with Sketches of Its Cities, Villages and Towns, Educational, Religious, Civil, Military, and Political History, Portraits of Prominent Persons, and Biographies of Representative Citizens. Evansville, IN: UniGraphic, Inc., 1976.

- Le Baron, William. The Past and Present of Lake County, Illinois. Containing a History of the County–Its Cities, Towns, &c., a Biographical Directory of Its Citizens, War Record of Its Volunteers in the Late Rebellion, Portraits of Early Settlers and Prominent Men, General and Local Statistics, Map of Lake County, History of Illinois, Illustrated, History of the Northwest, Illustrated, Constitution of the United States, Miscellaneous Matters, Etc., Etc. Google Books. Chicago, IL: Brookhaven Press , 1877. Pg. 227-232, 297-298. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Past_and_Present_of_Lake_County_Illi/wE40AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

- Dretske, Diana. What’s in a Name?: The Origin of Place Names in Lake County, Illinois. Wauconda, IL: Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County, 1998. Pg. 47, 62.

- Dunn, Robert O. “County Seat Was Located in Town.” The Independent-Register. March 22, 1973. Pg. 10.

- Carroll, Charles Edward. Ms. Essay Written by C.E. Carroll on the County Seat Controversy. Libertyville, 1956.

- “Political History of Lake County – Number Seven.” Little Fort Porcupine and Democratic Banner. June 4, 1845. https://newscomwc.newspapers.com/image/699048362/.

- Meads, Joe. “The Courthouse Controversy.” The Independent-Register. December 22, 1960.

- Osling, Louise A. Historical Highlights of the Waukegan Area. Waukegan, IL: City of Waukegan, 1976.

- Eskridge, Larry. “Waukegan ‘Stole’ Libertyville’s County Seat.” Daily Herald. April 14, 1982. Pg. 12.

- Meads, Joe. 1960.

- Carroll, Charles Edward. 1956.

- Carroll, Charles Edward. 1960.

- Carroll, Charles Edward. “History of Libertyville.” Libertyville: Cook Memorial Public Library, n.d. Pg. 33-35, 37, 45-47, 49, 75, 87-91, 95-97

- An act for the permanent location of the county seat of Lake County, 13 §. Laws of the State of Illinois (1843). https://archive.org/details/lawsofstateofill1843illi/page/114/mode/2up.

- Dretske, Diana. “Lake County’s First Courthouse.” Web log. Lake County, Illinois History (blog). Bess Bower Dunn Museum, August 12, 2010. http://lakecountyhistory.blogspot.com/2010/08/lake-countys-first-courthouse.html.

- Dretske, Diana. 1998.

- Photos courtesy of the Waukegan Historical Society, Bess Bower Dunn Museum of Lake County and Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History