The 3rd annual Lake County History Symposium, held at the Adlai E. Stevenson Home on April 30, focused on Immigrant Stories. Attendees heard about Polish Pioneers in Illinois, the experiences of a select group of families from the “Irish Hills” of Newport Township and the origins of the Lake County’s numerous Irish place names, and the William Boot family which came to Ela Township from England in 1841. They also learned about the Scots who lived or worked in Lake Forest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries helping to build Lake Forest Hospital, Lake Forest High School, and companies such as Carson Pirie & Scott and Quaker Oats. I spoke about Frederick Grabbe, born October 16, 1842 in Hanover, Germany who came to the U.S at about age 3 in 1845 with his father Ludwig Grabbe, mother Dorothea Myer Grabbe (1821-1868) and younger brother Henry Grabbe (1844-1920). Frederick would go on to serve in the Civil War, pioneer the floating apiary, and bring acclaim to Libertyville through his Abana Spring Water bottling company.

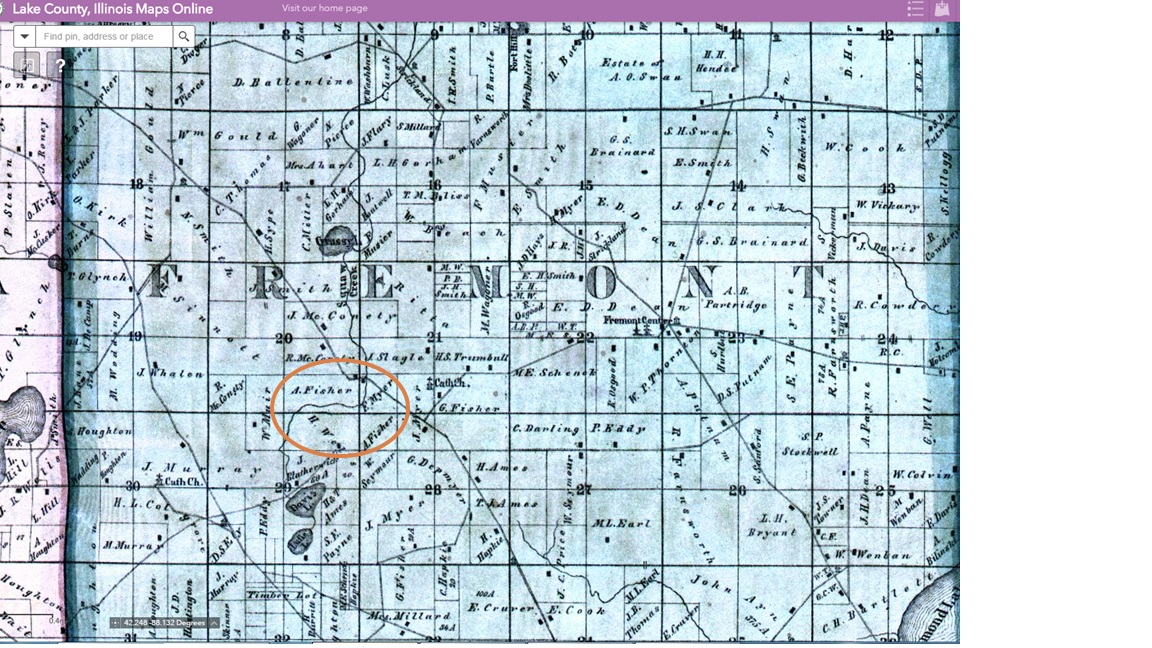

Little information is known about the family’s early years in the United States. Frederick’s obituary says that his father, Ludwig, died while the family lived in Chicago, but no death date is mentioned. I’ve yet to find anything verifying the location of the family in Chicago or in Fremont Township in the late 1840s or early 1850s. We do know that Ludwig had died by 1855 as Frederick’s half-sister Emma Fisher (1855-1930) was born in that year to Dorothea and her new husband August Fisher, a farmer in Fremont Township. Frederick probably grew up on the Fisher farm (shown here on the 1861 Fremont Township plat map) with his brother Henry, Emma, and half-brother August (1858-1903).

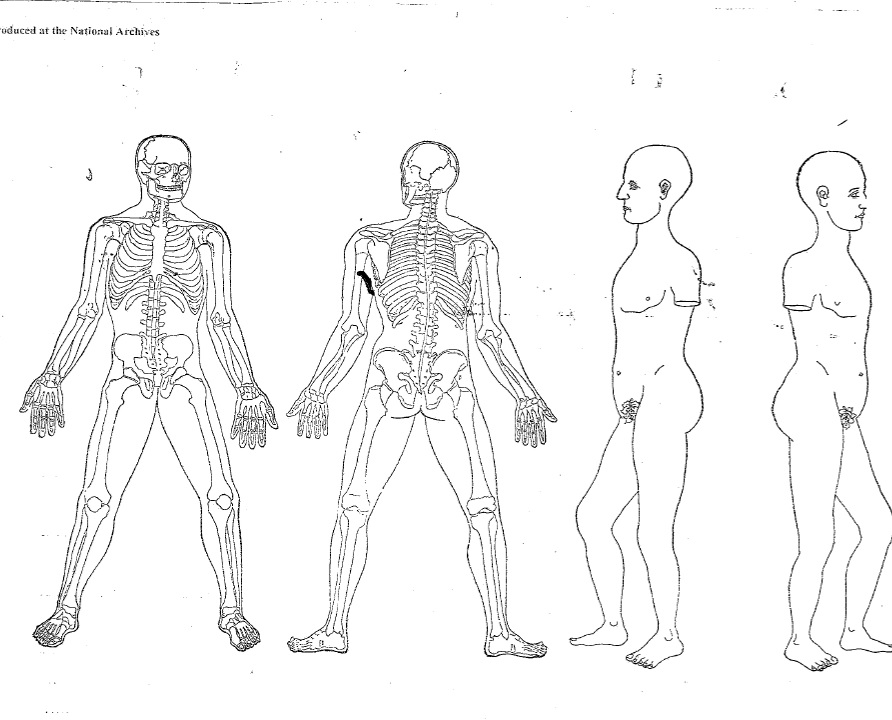

Frederick enlisted in the army in October 1861, just months after the outbreak of the Civil War. He was only 18 years old. He served in the 51st Illinois Infantry, Company G, participating in 31 battles over his military career according to his obituary. A seminal battle for Frederick Grabbe, and Lake County soldiers in general, was the Battle of Chickamauga in northern Georgia near Chattanooga, TN. Over two days, September 19-20, 1863, the 51st Illinois Infantry lost 90 out of 209 men. On the first day of the battle, Frederick received a musket ball/gunshot wound to the left shoulder as noted below in his pension records. He was taken to Cumberland Hospital in Nashville, TN for treatment. He was in the hospital for 3 months on account of contracting small pox while in the hospital recovering. The wound never fully healed, and he would have shoulder issues for the rest of his life, but he returned to duty January 31, 1864. In February 1864 he was promoted to sergeant and just about one year later he was promoted to lieutenant. Frederick received an honorable discharge in September 1865 and arrived at Camp Butler, near Springfield, IL, in mid-October for payment and discharge. Although he mustered out as a lieutenant, he was often called Captain Grabbe by friends.

It’s not clear where Frederick went or what he did immediately following the war. His Civil War pension records indicate he lived in Kansas for 4 years and then New Orleans for 4 years before settling in Libertyville, IL, but the numbers don’t quite add up.

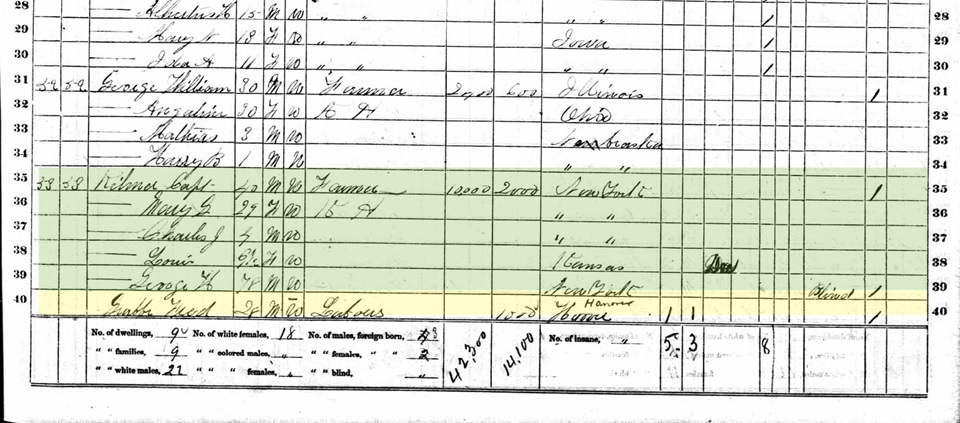

We know that he was definitely in Kansas by June 1870 when the census was taken. He was living with, and likely working for, Captain C. B. Kilmer, a former whaling vessel captain and “one of the prominent and wealthy railroad men of the West” according to a profile of his brother-in-law, Edgar Green, in the Portrait and Biographical Album of Lake County. Kilmer was married to Mary A. Gray, sister of Elizabeth “Libbie” Gray who would become Frederick’s wife within a couple of years. It is not known exactly how Frederick and Elizabeth met and whether it was in Fremont Township or later in Kansas. Libbie’s family had moved to Fremont Township from the state of New York in 1862 and purchased a small farm in northwest Fremont township while Frederick was away in the war. But in 1868, the Grays sold the land and Libbie’s parents moved to Kansas, likely to be near their daughter Mary and son-in-law Capt. Kilmer. Being only 19 at the time, Libbie probably moved out to Kansas with her parents. Was Frederick already in Kansas when the Grays arrived or did he follow them there? In either case, a relationship was struck up, or rekindled, between Frederick and Libbie and they married on Christmas Day in 1872 in Kansas. The couple would go on to have three sons – George (1874-1940), Charles (1891-1920), and Maurice (1895-1971).

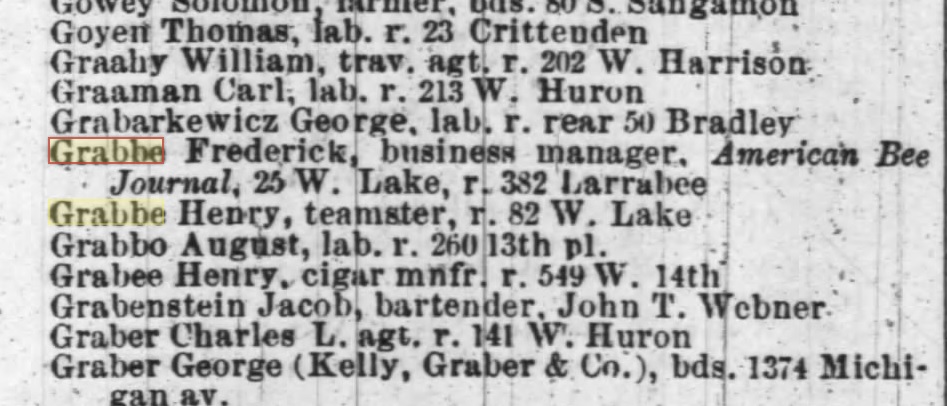

While in Kansas, Frederick pursued beekeeping which would remain a passion of his for the rest of his life. In 1872, he won 1st premium for Best Yield of Honey and 2nd premium for Best Display of Honey at the Kansas State Fair. Also that year, he was granted a patent for the Kansas Bee-Hive. An advertisement in the April 1873 American Bee Journal extolled its virtues. The advertisement also shows that Frederick had moved back to Illinois with an office at 25 W. Lake Street in Chicago. Captain Kilmer served as his “Western Manager” back in Kansas.

Checking the 1873 Chicago City Directory (below), we find that in addition to his hands-on work with bees and hives, Frederick served as business manager of the American Bee Journal with a residence at 382 Larrabee. Frederick was also a part-owner of the publication at one time. By 1874, Frederick and Libbie had moved to Wilmette where their first son, George, was born on June 4 of that year. The family was living in Wilmette when Frederick departed (with or without his family is unknown) to go on what I like to call “Frederick’s Big Adventure.”

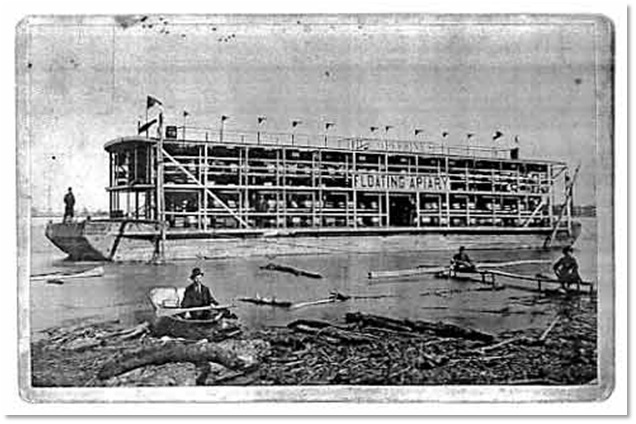

It was in late 1876 that Frederick moved to New Orleans to begin work with C.O. Perrine of Chicago on a floating apiary. Perrine had the idea to put bee hives on a boat and follow the blooming of flowers and trees up the Mississippi River from New Orleans to St. Paul, MN therefore extending the nectar gathering time. In January 1877, the gentlemen set up saw mills on St. Charles Avenue in the Seventh District of New Orleans and began cutting out material for 1000 hives.

Perrine purchased two gunwale barges and built tiers for bee hives – large enough to hold 1000 colonies of bees on each. In addition to Perrine and Frederick, who was to be in charge of “bee management,” there was a crew of 15-20 men. Sleeping quarters, as well as space for making and repairing hives and gathering honey, were below deck, in a 10 x 7 ft. space. The cooking and dining would take place on the James A. Fraser, the stern wheel boat towing the fleet. The expedition was scheduled to leave April 1, 1878, but it was delayed to May 13. The second barge was not finished on time.

Once the voyage was underway, the boats would move 30-40 miles per night and dock at a favorable spot during the day in order to release the bees for the day to gather honey. According to news reports, some bees were lost each day, but, on the plus side, other “vagrant” bees were picked up. [This makes me picture bees with little hobo sacks thrown over their shoulders!] Unfortunately the endeavor lost 5 weeks due to engine trouble and the need to stop for repairs. Due to the delays, the barges were not able to keep up with the blooms and the barges were abandoned 300 miles north of New Orleans. The bee hives were transferred to a steamboat, taken to St. Peter’s, MO, 40 miles north of St. Louis, and put ashore.

Ultimately it was not a financially successful venture. The trip cost more than $20,000 (over $475,000 in today’s dollars). However, Perrine thought it successful as a proof of concept and made plans to try again the next spring. It’s not clear whether the second attempt was made and if so, if Frederick was part of the follow-up venture. In either case, Frederick had returned to Libertyville by July 1880 where he was included in the U.S. Census for Libertyville with Libbie, son George, now 6, and mother in law Elizabeth Gray.

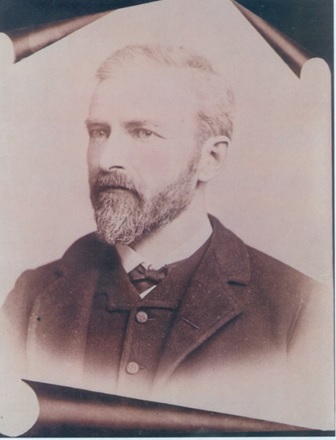

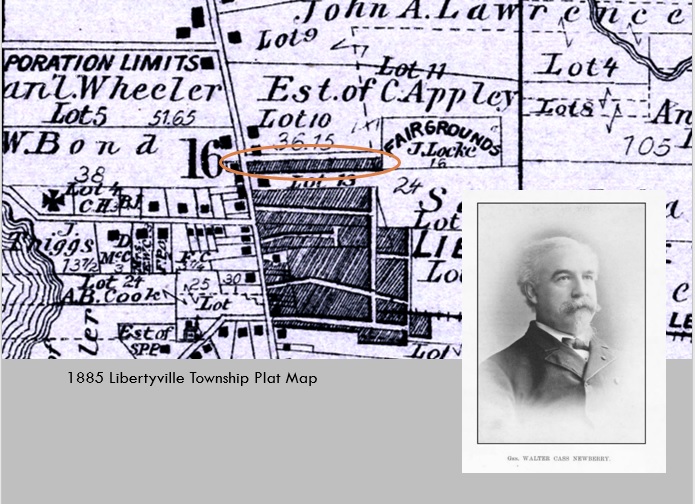

Frederick continued his work with bees back in Illinois, but he was also involved in various other enterprises. He partnered with General Walter C. Newberry on several projects. General Newberry was born in New York in 1835 to a well-to-do family and was the nephew of Walter Loomis Newberry, founder of the Newberry Library in Chicago. He served in the Civil War in the 81st New York Volunteers where he moved up the ranks and was brevetted as a brigadier general in March 1865 for gallantry in the Battle of Dinwiddie Courthouse, VA. After the war he served as mayor of Petersburg, VA and Superintendent of Public Property for the State of Virginia before moving to Chicago in 1876. In Chicago, he served two terms as postmaster and as a U.S. Representative from 1891-1893.

General Newberry’s relationship with Libertyville may have started as early as 1853. According to a letter published in the Chicago Evening Post several years after his death, General Newberry came through Lake County and Libertyville on his way to Wisconsin and was impressed with the beauty of the prairie and flora along the Des Plaines River. In 1880 he purchased a little over 12 acres in Libertyville from Samuel Moore running east from present day Milwaukee Avenue and Newberry Avenue around the site of the current Liberty Theatre. Newberry kept his horses here and Frederick pastured and tended the horses.

Always the entrepreneur, Frederick saw a need for a flax mill to serve Lake County farmers. He built a flax mill on land owned by General Newberry, but seems to have only operated it for a few years. A chattel deed from April 1883 shows Frederick sold the mill building and machinery. It was also in 1883 when Newberry subdivided his Libertyville property. Frederick helped to sell the lots.

Frederick is perhaps best known for his spring water enterprise – Abana Spring Water.

Libertyville was so proud of its spring water that at least 7 pages are devoted to it in the 1897 promotional publication Libertyville Illustrated. [Hear more about Libertyville Illustrated through a previous podcast.] At one point there was a string of underground springs running down Lake Street which then took a jog a bit north to Newberry Avenue. Libertyville Illustrated reports that the first well was drilled in 1878 and that by the 1890s each home on Newberry had a flowing well. Water was reached at only a depth of 50-200 ft and would gush above ground level. The water temperature held steady at 52°F year-round leading some homes to use the water as refrigeration in their basements.

Local histories report that Frederick partnered with Newberry to establish the Libertyville Mineral Springs Company about 1880, but it may have been later. Since Frederick operated a mill on land owned by Newberry, it is possible he operated a bottling works on Newberry’s land also, but no documentary evidence of this has been found. We do know that Frederick bought the spring property from Newberry (Lot 3, Newberry’s Addition) in 1891. The first newspaper article found about the spring (above) is from 1897. (The spring is referred to as the Hygienic Spring and not yet as Abana Spring.) A blurb in the October 1897 American Bee Journal mentioned that Frederick dropped by the office and in addition to his bees “he is interested in the sale of a very fine table or drinking water that flows at the rate of six gallons per minute from a spring on his place.”52 A blurb about the same time the following year, 1898, in the same publication, stated that he was “Still keeping some 30 colonies of bees, securing about 1000 pounds of honey the past season, has been getting into the spring and mineral water business the past year or more.”72 In 1899, Frederick signed an agreement with Henry Mitchell of Chicago granting permission for Mitchell to market and sell water from “Hygiene Spring.” By the 1900 US census, Frederick’s occupation is listed as “shipper of mineral water.” These clues would seem to support a later date, circa 1897, for the formation, or at least ramp up, of the bottling concern.

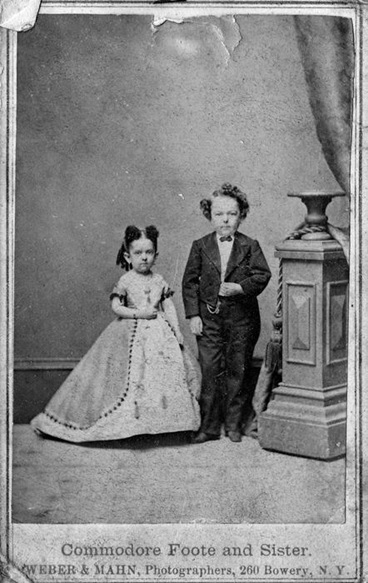

In the 1897 Libertyville Illustrated, the spring water received some celebrity endorsements. Eliza Nestel, known as the Fairy Queen, and her brother Charles, known as Commodore Foote, famous “little people” of the era were frequent visitors to Libertyville. Commodore Foote is quoted as saying that he had “travelled all over Europe…and visited nearly all its famous watering resorts, but I have never drank water to compare with that of Libertyville. Everyday I visit the Hygeinia Spring, and drink its water in the hotel.” [Libertyville Hotel – corner of Milwaukee and Church Street, today’s Lovin’ Oven]. His sister said “I have derived great benefit from it, during the past two months, I have gained 8 pounds, which is considerable for one who never weighed more than 60 pounds. ”

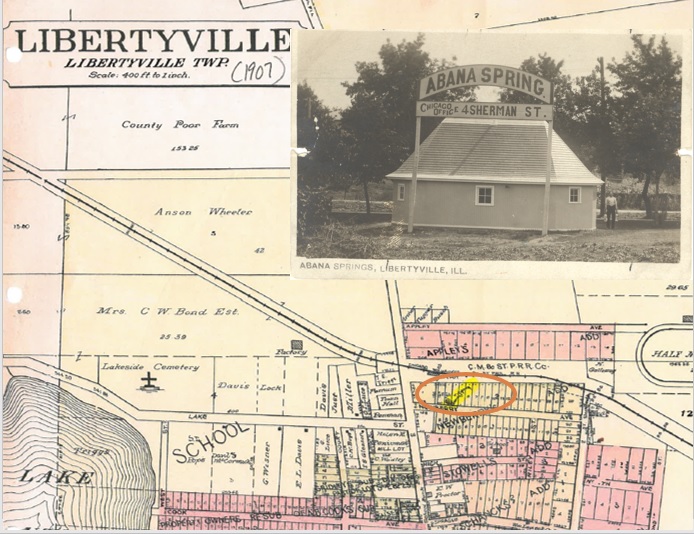

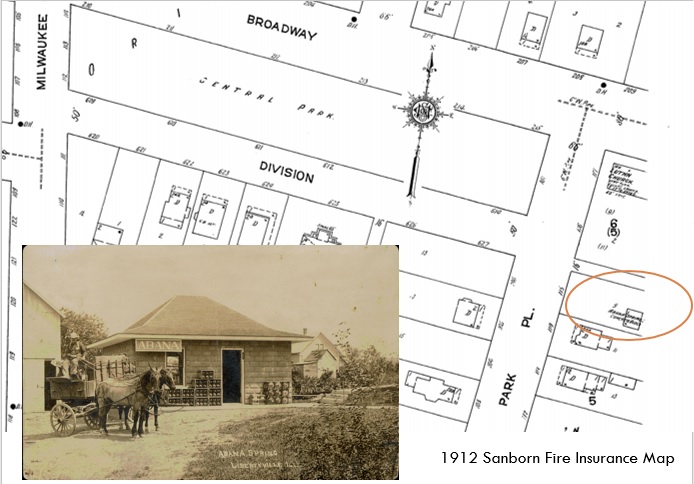

The business name changed to Abana Springs, referring to an ancient river near Damascus, about 1902. The frame building shown here stood on Newberry Avenue. The unidentified man is carrying the water in demijohns – 5 gallon containers. You could purchase two demijohns for $1.00 in 1909.

The spring was very successful. In a 1903 special edition of the Lake County Independent, Frederick was lauded as the “first citizen of Libertyville to exploit the medicinal waters of the village…” Frederick experienced great demand from residents of Chicago and the North Shore and by 1908, could not keep up with orders from his single spring. So he expanded. He purchased land with a flowing spring on Park Place (above) to supplement the Newberry Avenue supply. He built a concrete block building for bottling which supplied water to the Armour meat packing family as well as other North Shore residents.

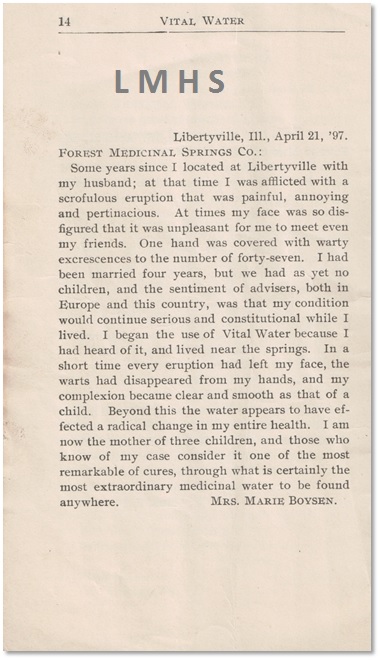

Frederick was also involved with the Forest Medicinal Springs Company of Libertyville. A sulphur springs existed on Forestspringfarm, owned by C. C. Copeland, near the Rockland Road Bridge over the Des Plaines River east of Libertyville. This site was said to have been the location of a Native American encampment where they used the water as a cure for many illnesses. Frederick is listed as the main point of contact for Vital Water in an 1897 newspaper article announcing the publication of a 16 page leaflet extolling the virtues of the sulphur water. One item of note in the pamphlet is a page concerning handling. The water was bottled in amber bottles and needed to be kept in a cool dark place. Local histories say that if the suplhur water was exposed to the air for a few days, it turned the color of milk. Sunlight also caused a chemical reaction which could cause clear bottles to explode, therefore the water was sold in amber bottles to reduce exposure to light. Vital Water also had its share of endorsements and testimonials, although not from celebrities, several of which were published in that 16 page leaflet. Here is one of the more spectacular:

In addition to his business enterprises, Frederick was a Mason for over 52 years, having first joined the Rising Sun Lodge of Hainesville and then transferred to Libertyville Lodge 492. He was also a member of Acme Camp of Modern Woodmen of America. Frederick passed away October 14, 1915. He had recently returned from the Illinois State Fair in Springfield where he served as a judge of honey. He was not feeling well and was admitted to Jane McAllister Hospital in Waukegan where he died. Services were held at his home on Park Place on his 73rd birthday. Burial was at Ivanhoe Cemetery with full Masonic services.

In a 1963 letter to the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, Frederick’s grandson, Kenneth Grabbe, wrote that the spring water business ended with Frederick’s death in 1915. It is possible it went on a bit longer as the 1920 census (taken January 15) shows Frederick’s son, Charles, involved in the retail spring water business and employed on his own account. Yet, Charles died from pneumonia less than a month later. His obituary indicated that he had been confined to his home for a few years suffering from rheumatism. If the spring was still operating, it is unlikely Charles was doing the bottling. In any case, there is no indication that Abana Spring continued in to the 1920s.

I’d like to conclude with just a few tributes to Frederick Grabbe…

¨“…a man of large experience, practical, energetic and an untiring worker.” –C. O. Perrine. Gleanings in Bee Culture, April 1878

¨“…among the most dignified of Libertyville’s old soldiers being distinguished by his straight carriage and white hair. With the exceptions of one shoulder which was injured during the war, he was exceptionally fine appearing.” —Lake County Independent, October 15, 1915, p.4

¨“unique character in the best sense of the term” –C.E. Carroll, “Frederick Grabbe”, unpublished manuscript, c.1955

Sources

- “Abana Spring, F. Grabbe, Manager.” The Industrial News [Chicago,IL] 14 Aug 1909: 19. Print.

- “The American Bee Journal.” Bee-keeper’s Magazine Jan 1874: 17. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- Baldridge, M.M. “Migratory Bee-keeping – Something from a veteran.” The Bee Keeper’s Review 10 Jan 1890: 7. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- “Bee Items from New Orleans.” The American Bee Journal Feb. 1877: 46. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- “Bees & Queens.” Advertisement. The American Bee Journal 9 Apr 1886: 238. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- “A Big Honey Speculation.” From the St, Louis G. New York Times (1857-1922): 2. Jul 17 1878. ProQuest. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- Carroll, C.E. “Abana Spring.” TS 4377.2, Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

- Carroll, C. E. “Frederick Grabbe.” TS 2179, Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

- Carroll, C. E. “Spring Water.” TS 2178, Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

- “The Centennial Honey Show.” The American Bee Journal December 1876: 297. Google Books. Web. 19 Apr 2017.

- City Directories for Chicago, Illinois. Fold3. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- “Death Takes Gen. Newberry.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922): 7. Jul 21 1912. ProQuest. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- “Death Takes Rail Man, Geo. Grabbe.” Independent-Register [Libertyville, IL] 1 Feb. 1940: 4. Print.

- Dretske, Diana. “Jane Strang McAlister, Milburn.” Web blog post. Lake County, Illinois History. Lake County Discovery Museum. 5 Aug 2010. Web. 4 Mar 2015.

- “Edgar Green.” Portrait and Biographical Album of Lake County, Illinois. Containing Full Page Ports. and Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens of the County, Together with Ports. and Biographies of All the Presidents of the United States and Governors of the State. Chicago: Lake City Pub., 1891. Print.

- Federal Military Pension Application – Civil war and Later for Frederick Grabbe. National Records and Archives Administration, Washington, D.C.

- “Fred Grabbe.” The News-Sun, May 12, 1993, Section D, Special Souvenir Edition reprint of the Lake County Independent, September 25, 1903. Print.

- “A Fine Analysis.” Lake County Independent 6 Aug. 1897: 1. Print.

- “A Floating ..” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922): 3. Jul 24 1878. ProQuest. Web. 21 Apr. 2015.

- “A Floating Bee Palace.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922): 7. Apr 08 1878. ProQuest. Web. 21 Apr. 2015 .

- “Freemont Township.” Lake County, Illinois map of 1861 : with landowners index. Edited by Julie Weber & Aileen Potterton Hapke. Libertyville, Ill. : Lake County (IL) Genealogical Society, 1997. Print.

- “Funeral of Fred Grabbe Held on His Birthday.” Lake County Independent 22 Oct. 1915: 4. Print.

- “General Newberry’s Tribute.” The Chicago Evening Post, 12 September 1925.

- Grabbe, F. “C.O. Perrine’s Scheme; Why It Failed; Large Profits in Getting Bees from South.” The Bee Keeper’s Review 10 May 1890: 83. Google Books accessed 21 Apr 2015.

- Grabbe, Frederick, inventor. Improvement in Bee-Hives. US patent 131,610. September 24, 1872.

- Grabbe, G. K. “Letter regarding Abana Springs.” Letter to Mr. Allen Botimer. 13 Sept. 1963. MS. Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, Libertyville, Illinois.

- Graff, J.L. “A House Full of Bees. Migratory Bee-Keeping on the Mississippi 25 years ago.” Gleanings in Bee Culture 1 Nov 1890: 697. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- Halsey, John J. A History of Lake County, Illinois. Philadelphia: R.S. Bates, 1912. Print.

- Henry, William E. “Lt. Frederick Grabbe, Co. G, 51st Illinois Inf.” 51st Regiment Illinois Volunteers. 19 Feb. 2006. Web. 13 Feb. 2015. <http://51stillinois.org/grabbe.html>.

- Illinois. Lake County. Corporations, 1870-1935. Lake County, IL Recorder of Deeds Land Records Search. Web.

- Illinois. Lake County. Deeds, 1870-1935. Lake County, IL Recorder of Deeds Land Records Search. Web.

- Illinois. Lake County. Mortgages, 1870-1935. Lake County, IL Recorder of Deeds Land Records Search. Web.

- Illinois. Lake County. Plats, 1870-1935. Lake County, IL Recorder of Deeds Land Records Search. Web.

- Illinois. Libertyville, Lake County. 1880 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital images. Ancestry Library Edition. http://ancestrylibrary.proquest.com/: accessed 17 July 2013. From National Archives microfilm T9, roll 314.

- Illinois. Libertyville, Lake County. 1900 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital images. Ancestry Library Edition. http://ancestrylibrary.proquest.com/: accessed 17 July 2013. From National Archives microfilm T623, roll 221.

- Illinois. Libertyville, Lake County. 1910 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital images. Ancestry Library Edition. http://ancestrylibrary.proquest.com/: accessed 10 July 2013. From National Archives microfilm T624, roll 301.

- Illinois State Board of Agriculture. Transactions of the Department of Agriculture of the State of Illinois with Reports from the County Agricultural Societies for the Year 1915. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Journal Co., 1916: 260. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- “Illinois State Fair Exhibit.” The American Bee Journal Nov 1907: 715. Google Books. Web. 21 Apr 2015.

- “Increase Output of Abana Spring.” Lake County Independent 2 Oct 1908: 5.

- Iversen, Elizabeth “Libby” Grabbe. Personal interview. 1 Mar 2015.

- Kansas. Township of Soldier, Shawnee County. 1870 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital images. Ancestry Library Edition. http://ancestrylibrary.proquest.com/: accessed 8 February 2015. From National Archives microfilm M593, roll 442.

- Kansas. State Board of Agriculture. Transactions of the Kansas State Board of Agriculture. S.S. Prouty, Public Printer, Topeka, KS, 1873. Google Books. Web. 4 Apr 2015.

- “Kansas Beehive.” Advertisement. The American Bee Journal Apriil 1873: 266. Google Books. Web. 19 Apr 2017.

- Lake County (IL) Genealogical Society. Cemetery Committee. Ivanhoe cemetery and Swan cemetery : tombstone inscriptions and burial records, Fremont township, Lake county, IL. Libertyville, IL : Lake County (IL) Genealogical Society, 1997.

- “Libertyville, IL, 1907.” Digital Sanborn Maps, 1867-1970. Web. 26 Feb 2015.

- “Libertyville, IL, 1912.” Digital Sanborn Maps, 1867-1970. Web. 26 Feb 2015.

- Libertyville Illustrated. Ed. Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society. Marceline, Mo. : Walsworth Pub. Co., 1993. Revision of the 1st ed. published: Chicago : Kehm, Fietsch & Miller Co. Press, 1897. Print.

- Libertyville Telephone Directory 1913. Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation. Illinois Digitial Archives. Cook Memorial Public Library District, 24 Feb. 2010. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

- Libertyville Telephone Directory 1929. Reuben H. Donnelley Corporation. Illinois Digitial Archives. Cook Memorial Public Library District, 24 Feb. 2010. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

- “Lieutenant Fred Grabbe Dies in Waukegan Hospital.” Lake County Independent 15 Oct 1915: 4. Print.

- “‘Miracle’ Water Flowed from Famous Wells of Libertyville.” Daily Herald [Arlington Heights, IL] 4 June 1986. Print.

- “Mr. F. Grabbe..” The American Bee Journal 14 Oct 1897: 2650. Google Books. Web. 19 Apr 2017.

- “Newberry, Walter C.” Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress, 1774-Present. Web. Accessed 3 Apr 2015.

- “Origin of the name Abana.” Lake County Independent 17 Sept 1902: 2. Print.

- “Our Water Was Yummy.” Independent-Register [Libertyville, IL]. Print.

- “Pure drinking water.” Lake County Independent 3 Nov. 1899: 5. Print.

- Schumpert, Dale. “Frederick Grabbe (1842 – 1915) – Find A Grave Memorial.” Find A Grave. 27 July 2012. Web. 08 Feb 2015.

- Standard atlas of Lake County, Illinois : including a plat book of the villages, cities and townships of the county … patrons directory, reference business directory … Chicago : Geo. A. Ogle, 1907. Print.

- U.S. Geological Survey. “State of Illinois State Geological Survey. Illinois-Wisconsin Waukegan Quadrangle.” Map. Scale 1:62500. U.S Geological Survey, 1908. Print.

- Vance, J. W. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois Containing Reports for the Years 1861-66. Springfield, IL: H.W. Rokker, State Printer and Binder, 1886. Print.

- “Vital Water Cures: Fame of Libertyville’s Springs Spreading Far & Near.” Lake County Independent 14 May 1897: 1. Print.

- “Voices from among the hives.” The American Bee Journal September 1874: 217. Google Books. Web. 19 Apr 2017.

- Watters, Laura. “Old-timers said water was elixir.” The Herald [Arlington Heights, IL] 29 Mar 1978: Section 1, p.2. Print.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1901. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1903. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1905. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1908. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1913. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1916. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1922. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- Waukegan, Illinois, City Directory, 1925. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

- “Weekly Budget.” The American Bee Journal 20 Oct 1898: 666. Google Books. Web. 19 Apr 2017.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History