Welcome back to my series of posts on local history! While looking for a topic for this post, I realized that we have somehow neglected to write about the history of a Libertyville institution: Lambs Farm! Since its inception as a small pet store in the fall of 1961, Lambs Farm has made it its mission to provide people with cognitive disabilities with “vocational, residential and recreational programs” that enrich their lives (Lambs Farm 2013). Before I begin however, I just want to warn readers that some of the terms used in this post might be considered offensive, and that I am only using them when they appear in the names of historical organizations or to better illustrate historical living conditions for people with cognitive disabilities. So, let’s delve into the rich and often surprising history of Lambs Farm, from the stories of people living more fully than society thought possible, to visits by playboy bunnies and First Ladies!

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, if people with cognitive disabilities were lucky, they lived with their family and were kept out of sight thanks to ugly laws, laws aimed at keeping “any person, who is diseased…or deformed in any way…[from] expose[ing] himself to public view” (Albrecht 2006, p. 1575). If they were unlucky, they would become one of the approximately 1.2 million people living in institutions where residents were sometimes chained to their beds for days or in some cases, sterilized. Terms like retarded or mongoloid idiots could be found in professional medical journals and there were no laws mandating services for children or adults with special needs. Some groups like the Illinois Council for Mentally Retarded Children (today’s Arc of Illinois) did try to improve the lives of people living with disabilities and provide them with better access to education, but with their limited resources they could only do so much. As a result, parents of children with cognitive disabilities were forced to create a makeshift education system, renting whatever space was available and hiring teachers, who often had no experience working with special needs students, in order to provide some modicum of education for their children. One of these schools was the Bonaparte school for mentally retarded children.

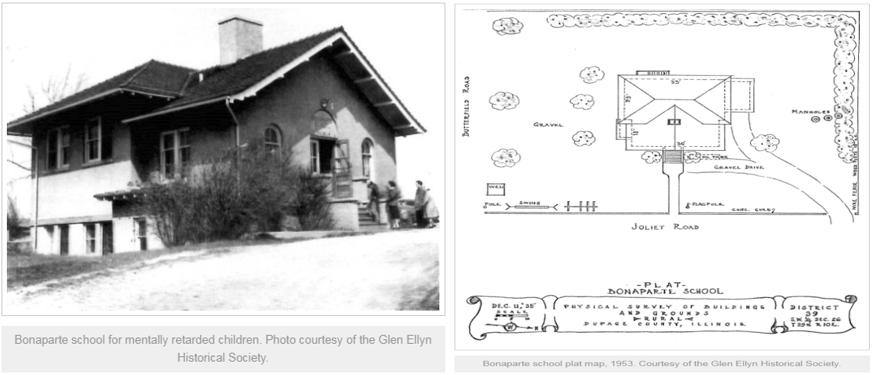

Built in 1844 and located at 540 Crescent Boulevard in Glen Ellyn, the school was an old, drafty former country schoolhouse that, until parents of children with cognitive disabilities, looking for somewhere to teach their children, had convinced the county to let them rent for $1.00 a day ($8.97 today), had stood vacant since it had been detached from the school district in 1925. To help finance the rent, student’s parents, along with members of the Junior Woman’s Club and other charitable organizations, sold copies of Angel Unaware by Dale Evans Rogers for a few cents a copy. By 1954, the school had 44 students ranging in age from 6 to 25 years old. Despite the best of intentions of the parents and teachers however, the school more often than not failed the very people it was meant to help. Students either wandered the school aimlessly, sat curled up against the wall, or were forced by teachers to recite multiplication tables in the vain hope that by learning something students normally learn, they would become “normal”. That would begin to change, however, with the arrival of Bob Terese in 1957 and Corrine Boren in 1958.

Built in 1844 and located at 540 Crescent Boulevard in Glen Ellyn, the school was an old, drafty former country schoolhouse that, until parents of children with cognitive disabilities, looking for somewhere to teach their children, had convinced the county to let them rent for $1.00 a day ($8.97 today), had stood vacant since it had been detached from the school district in 1925. To help finance the rent, student’s parents, along with members of the Junior Woman’s Club and other charitable organizations, sold copies of Angel Unaware by Dale Evans Rogers for a few cents a copy. By 1954, the school had 44 students ranging in age from 6 to 25 years old. Despite the best of intentions of the parents and teachers however, the school more often than not failed the very people it was meant to help. Students either wandered the school aimlessly, sat curled up against the wall, or were forced by teachers to recite multiplication tables in the vain hope that by learning something students normally learn, they would become “normal”. That would begin to change, however, with the arrival of Bob Terese in 1957 and Corrine Boren in 1958.

A daydreamer who “bore[d] easily”, Robert “Bob” Terese was a veteran of the Second World War who, after returning to Chicago in 1946, had enrolled at DePaul University to study physical education (Unsworth 1990, p. 29). Dropping out only a few credits short of his degree in 1950, he made up for it by meeting and married Mary Miller later that year. Bob drifted from job to job until September 1957, when he took a job as a bus driver for students attending Bonaparte. Within a few hours he would try to quit, but was persuaded to stay by desperate parents who were unable to find a replacement. Driving the students to and from school left Bob with a lot of free time, time he spent looking for new ways to engage the students. He eventually started a simple exercise program (he had almost graduated with a degree in physical education), and later, a cooking program. Thanks to success of his programs, in the spring of 1958, Bob was hired as a full-time teacher.

Corrine Boren was born to a deeply religious farming family in Greenville, Ohio in 1915. Moving to Chicago so her father could study at the Moody Bible Institute, Corrine grew into a shy, practical young woman. Graduated from North Park University with a degree in Music Education, Corrine supporting herself by giving music lessons for which she charged $1 (around $8.97 today). Marrying Trevor Owen in 1938, she stayed home for a while to care for their children before returning to work as a part-time salesperson after her youngest had entered elementary school. In 1958, Corrine was visiting a friend named Jean Adams who happened to work at Bonaparte and was looking for someone to replace her as she was going on maternity leave that fall. Corrine didn’t have any experience working with special needs students, but looking for a new challenge, thought it was something she might be interested in trying. However, over the summer Corrie became anxious about her new position and so Jean arranged for her to meet her new teaching-partner, Bob.

It would be hard to say who was less impressed with the other. Bob had a short fuse and ran on instinct while Corinne was practical and had endless patience. They weren’t wrong in their assessment of the other’s shortcomings, but over time they realized that they complimented each other. Between classes they would discuss how they felt that what they were teaching their students had little to do with the kind of lives their students would go on to lead. During one of these conversations, Corinne wondered what would happen to the students after they left the school. It was a question that so haunted Bob, that that night after returning home, he tried to come up with a way for their students to live. His plan: a store that would provide both a purpose, the ability to make a living, and a place for them to live. Over the next few years he and Corrine continued to build on their store idea while experimenting with new ways to teach their students. By splitting their students up by their abilities and breaking down tasks into easy steps, they were able, through having them engage in various art projects, work on their students’ social skills. Decades later, Terese would say of these first tentative steps towards what would eventually become Lambs Farm that although they “knew [their] people”, they had “no idea what the hell we were doing” (Chicago Tribune 1991, p. 3). In 1959 Bob, looking for a better paying position, left Bonaparte to take a job at Chicago’s Hull House. Corinne joined him a year later in 1960.

Founded in 1889 by pioneering social workers Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, Hull House provided social, educational, and artistic programs to marginalized communities while acting as liaison to city charities and social service agencies. By the time Bob and Corinne arrived in 1960, Hull House was working with the Retarded Children’s Aid Society (RCA) to provide programs for people with disabilities. However, the board of directors had wildly divergent views on what kind of programs they should offer. Some, like the director of Hull House Russell Ballard, advocated for programs that kept students quiet and under control, while others argued that the higher-functioning students were capable of doing more, pointing to Hull House’s sheltered workshop program as a prime example. In addition to the increasingly toxic politics of the RCA, Hull House was also engaged in a protracted court battle to halt the demolition of the majority of their buildings to make way for the construction of the University of Illinois-Circle Campus. Despite all this, Bob and Corrine drew inspiration from Hull House’s workshop, seeing it as a place where they could engage with their students, challenging them to do more than they thought they could through doing meaningful work.

As the pieces for their workshop came together, Bob and Corrine began to look at different kinds of stores they could set up for their students. Inspiration struck when Bob remembered his experience working in a pet store, realizing that the repetitive tasks that had so bored him would be the perfect fit for their students. He was so excited that he called Corrine that evening, exclaiming “I’ve got it. A pet store!” (Unsworth 1990, p. 53). By the next morning, they had a name for the store: ‘The Lambs,’ a reference to the passage in John’s gospel where Jesus tells him to “feed my lambs”. With the support of their student’s parents, they approached the RCA’s director with their idea. Impatient, he told them to “stick [their] idea up there [on a bulletin board] with the hundred other ideas I get” (Unsworth 1990, p. 57). When the rest of the board found out about the two teachers talking about a new project without their knowledge, they were furious. So, just before Christmas 1960’s, Corrine and Bob were given an offer: they would be promoted to the head of their departments as long as they dropped their plans for the store. Refusing, they were both fired on the spot.

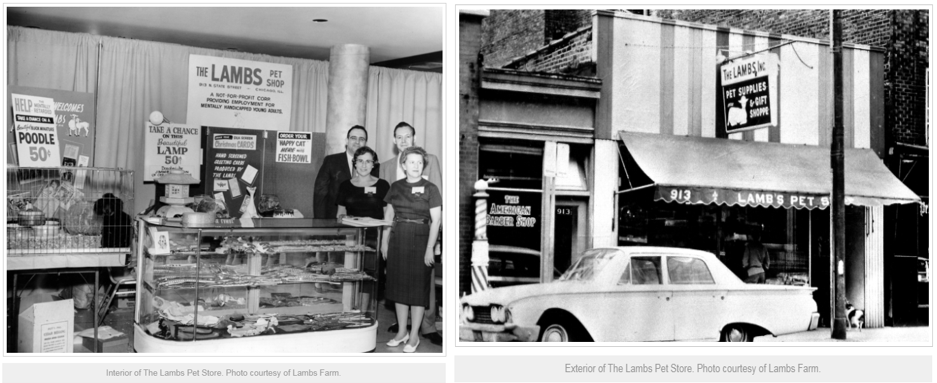

Over the next few months, the two took odd jobs to make a living. Bob continued his work at the railroad while Corrine worked as a florist for a short time, supplementing her income by selling subscriptions for Life Magazine. Despite the setback they continued their work on The Lambs Pet Store. They still had the support of their former student’s parents, and thanks to Corrine’s salesmanship, they were able to get supplies from L. Gifford Gardner, the owner of Pioneer Pet Supply, who provided them $8,000 ($ $68,109.73 today) worth of pet supplies. Eventually, they found a vacant storefront at 913 North State Street in Chicago. While the the floor was covered in debris, the toilet bowls were cracked and someone had taken the water heater, the location was perfect. Rent was $350 ($$2,949.90 today), but after much prayer, they were able to get the place rent free for the first five months (although cold calling the president of the company that still held the lease probably helped). The next few months were a blur of activity, but finally, the windows were filled with pet supplies, the tanks were filled with fish and the cages with bunnies. So, at 11:00 am on September 28th, 1961, almost nine months to the day that Bob and Corrine had been fired from Hull House, reporters from the (now defunct) Chicago American and Channel 7 news watched as Lambs Pet Store made its first sale.

I know that was a lot to cover, but now that I’ve (finally) gotten to the point that The Lambs Pet Store is open, it’s going to get a lot more interesting. So join me next time as Bob and Corrine guide Lambs farm from a small Chicago pet store to Libertyville institution, mingle with First Ladies, partake in goat-based yoga, and deal with the mob (seriously)!

Administrative History of Hull House Association. Accessed August 27, 2018. https://findingaids.library.uic.edu/sc/MSHHC_NO.xml#ref3.

Albrecht, Gary L. Encyclopedia of Disability. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2006.

Blair, Sheri. “Hull House Leaders Accept Defeat, Work to Help Uprooted Families.” Chicago American, May 14, 1963. Accessed August 31, 2018. https://hullhouse.uic.edu/hull/urbanexp/main.cgi?file=viewer.ptt&mime=blank&doc=966&type=pdf.

Brink, Lydia. “Tells of School for Mentally Retarded Children.” Oak Leaves (Oak Park), April 9, 1953. Accessed August 9, 2018. https://access.newspaperarchive.com/us/illinois/oak-park/oak-park-oak-leaves/1953/04-09/page-3/bonaparte-school-for-mentally-retarded-children?pci=7&psi=37&ndt=by&py=1950&pey=1959&ndt=ex&py=1953&search=y.

DeBrulye, K. C. “Harvest of Hope.” Chicago Tribune, February 10, 1991.

“Editorial Note.” Social Service Review 36, no. 2 (June 1962): 123-27. Accessed August 31, 2018. https://hullhouse.uic.edu/hull/urbanexp/main.cgi?file=new/show_doc.ptt&doc=670&chap=94.

“Hull House Fights Razing for Campus.” Chicago American, February 3, 1861. Accessed August 31, 2018. https://hullhouse.uic.edu/hull/urbanexp/main.cgi?file=viewer.ptt&mime=blank&doc=968&type=pdf.

Jane Addams’ Hull House. 1963. National Parks Service. In National Parks Gallery. Accessed September 10, 2018. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/da2a1e7b-4c82-47ef-96bc-619daa64c239/.

“Local Kids to Aid Retarded.” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights), November 12, 1959. Accessed August 20, 2018. https://access.newspaperarchive.com/us/illinois/arlington-heights/daily-herald-suburban-chicago/1959/11-12/page-149/bonaparte-school-for-mentally-retarded-children?page=3&psi=37&pci=7&ndt=by&py=1950&pey=1959.

“Mission & Programs.” Lambs Farm. Accessed July 31, 2018. http://www.lambsfarm.org/mission-programs/.

Photos courtesy of Lambs Farm, Glen Ellyn Historical Society, and the National Park Service.

Unsworth, Tim. The Lambs of Libertyville : A Working Community of Retarded Adults. Chicago, IL: Contemporary Books, 1990.

U.S. Congress. Joint commission on mental illness and health. Action for Mental Health: Final Report, 1961. 87th Cong., 1st sess., 1961. Accessed August 9, 2018. https://archive.org/stream/actionformentalh00join#page/n0.

Ward, Helen W., and Robert W. Ward. Glen Ellyn: A Village Remembered. Glen Ellyn, IL: Glen Ellyn Historical Society, 1999.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History