As our long-time readers may know, the Cook Memorial Public Library District works closely with the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society, whose resources we often make use of when doing research for our blog posts. With this in mind, and considering that the library serves both communities, I thought that I would take this opportunity to do a series of posts about the history of Mundelein, its many, many name changes, and the people who made it what it is today.

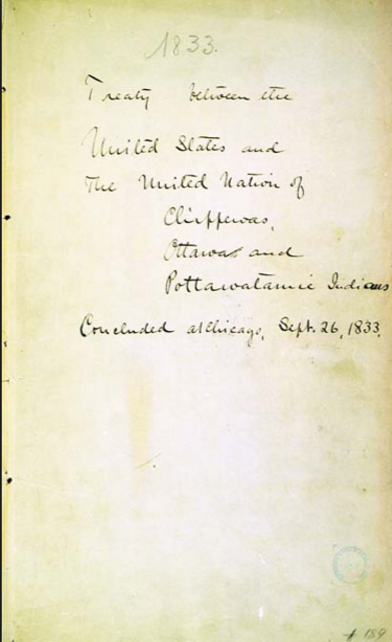

The origins of Mundelein date back to 1833 when the United States government acquired the ownership of the land from the Potawatomi through the signing of the Second Treaty of Chicago. Although officially belonging to the United States government, according to the treaty the tribe was supposed to retain real control of the land until August 1836. One can imagine these legal technicalities did not bother settlers however, since squatters soon took up residence. Among these squatters was Peter Shaddle, who in 1835 built the first log cabin on what is now St. Mary of the Lake Seminary. Surrounded by a grove of trees, the cabin was situated just in front of a corduroy road (a road made by placing sand-covered logs together) which itself was built on an old Native American trail. One year later in 1836, Shaddle sold his land to Solomon and Pauline Norton, who were joined later that year by the birth of their son James, possibly the first non-native person to be born in the area. Other settlers, among them the Paynes and the Clarks, whose family stories would become intertwined with that of the town, soon joined the quickly growing Norton family.

Many of these settlers had in their previous lives been mechanics, which at the time referred to millwrights, wheelwrights, and ship’s carpenters, many of whom had emigrated from England to escape an industrial and agricultural depression that was aggravated by heavy taxes. Due to their shared background and the many groves of trees surrounding their cabins, they named their quickly growing town Mechanics Grove. Over the next fifteen years, Mechanics Grove experienced a large influx of settlers. This expansion saw the appearance of the first local businesses, including one of the first general stores and rooming houses located on the east side of Diamond Lake, both built by Alexander Bilinski, as well as the construction of the first dedicated school. Built in 1837 and located on what is now the corner of Route 176 and 63 (Midlothian Road), Mechanics Grove School taught students from eight different grades, with teachers being paid around $6.00 a week (or $ 134.49 today).

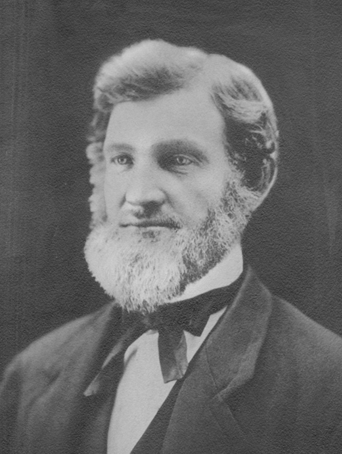

Among the many new arrivals were John and Birdett Holcomb. Originally from New York, John Holcomb had moved to Illinois in the late 1830’s where he met and eventually married his wife in DuPage County in 1846. The following year in 1847, the two moved to Mechanics Grove, where they purchased 80 acres of land for $1.25 an acre (the equivalent of $27.78 an acre today). This initial holding would eventually grow to encompasses between 300 to 356 acres of land, making John Holcomb one of the largest landholders in the area. John Holcomb quickly became involved with local political and religious life. Building a reputation as a “public-spirited man,” Holcomb served in multiple municipal offices, becoming a leading figure in the intellectual and social life of the town (Purcell, p. 2). By the 1850’s, Holcomb had become such an influential figure that the citizens of Mechanics Grove changed the name of the town to Holcomb. This would be the first of several names changes.

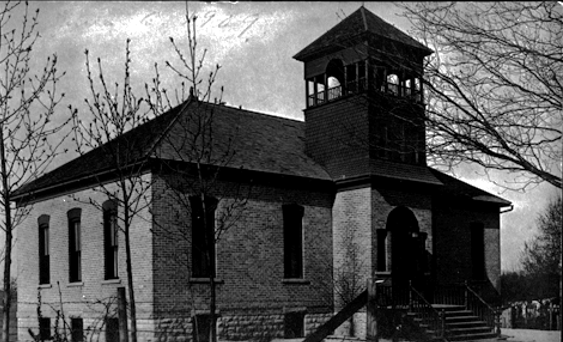

Life in Holcomb was violently upended with the outbreak of the Civil War in January 1861. As men from Holcomb, including G.H. Bartlett, E.C. Warrington, and J.E. Norton, left their families to fight for the union, neighboring Diamond Lake, having already made their anti-slavery stance clear even before the outbreak of war, voted to use the Diamond Lake Church as a safe house for the Underground Railroad. The war was horrible and bloody, but like all wars, it eventually ended and life in Holcomb continued.

By the latter half of the 19th century, despite relatively rapid expansion, Holcomb was still a very small, very rural community. That would change in 1885 when the Wisconsin-Central Railroad, the predecessor to the SOO Line, extended its tracks through Holcomb. The opportunities that the railroad brought to Holcomb cannot be understated. The growth that the railroad would bring must have been obvious, as John Holcomb himself donated 20 acres of land to the railroad. Holcomb quickly became a hub of commerce, with the construction of grain elevators for farmers looking to sell their grain in the city, a number of General stores, several hotels including Hardin’s Hotel, located on Maple and Lake, along with a number of houses for the town’s growing population. The railroad became such an important part of the town that shortly after its completion, and possibly at the suggestion of the railroad officials, the town voted to change its name for a second time, this time to Rockefeller, in honor of John D. Rockefeller’s brother William, who was an important stockholder in the company.

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, with a growing population and economic prosperity brought about by the railroad, the town voted to fund the construction of the town’s second school on West Maple Avenue. Opened in 1894, Lincoln School was a two-room schoolhouse that taught four grades in each room.

In 1905, a second railroad, this time the Chicago-Milwaukee Electric Railroad, extended its line through Rockefeller, with a new station built at Morris Avenue near Maple. In light of the economic boom brought by the extensions of not just one but two railroads, the businessmen of Rockefeller thought it was time for the next step and, in 1909, put forward a referendum to incorporate Rockefeller as a village. However, despite their seeming confidence in the matter, some of those in favor of incorporation privately feared that Rockefeller, which when the 1910 census was taken the following year only had 358 residents, did not actually have a population large enough to be incorporated. To get around this small technicality, proponents of the vote invited the residents of neighboring Diamond Lake to join Rockefeller. On January 25, 1909, the people of Rockefeller voted 55-22 to incorporate. A few weeks later, the Lake County Independent published a short ditty by an unnamed poet on the vote, writing:

“Oh little town of Rockefeller

So quiet in her way

Will yet be one of fame you’ll find

At no great distant day

Just a word of credit please

You may believe or not

No thanks for any outside help

She’s worked for what she’s got.”

This is how things stood in Rockefeller at the beginning of the twentieth century: a busy, prosperous hub of commerce, connected to Chicago and its neighboring cities by two railroads, having just incorporated and already on its third name. Join us again next month as we trace the growth of Rockefeller through the early 20th century, the beginnings of local politics, and learn just how much an acronym would shape the town’s future!

“The big dates in the history of Mundelein.” Independent-Register (Libertyville), June 28, 1984, sec. 2, p. 2-6.

DePuy, Cindy. “Mundelein — 73 years of history and progress.” Lake County Market/Journal, July 28, 1982.

History of Mundelein 1829-1939. MS, Library History Collection, Cook Memorial Public Library District, p. 2.

Killackey, Shawn P. Mundelein. Images of America. Chicago, IL: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Lodesky, James D. Polish Pioneers in Illinois 1818-1850. Xlibris, Corp., 2010, p. 180-81.

Maiworm, A. J. Rockefeller ILL. Postcard Collection, Cook Memorial Public Library District, LIbertyville.

Maley, Mark. “Mundelein: Remember its early days.” Independent-Register (Libertyville), February 2, 1984, p. 13.

Photographs courtesy of the Village of Mundelein, the Cook Memorial Public Library District, the Lake County Discovery Museum, and the Library of Congress.

Purcell, Connie, and Ricki Mandell. Memories of Mundelein. Fox Lake, IL: Mandell and Associates, 1984.

“Rockefeller.” Lake County Independent (Libertyville), January 29, 1909. Microform.

Schaul, Terry . Greetings from Mundelein “St. Mary of the Lake”. August 13, 1956. University of Saint Mary of the Lake Collection, Mundelein. Accessed March 7, 2016. http://www.idaillinois.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/nstmary01/id/384/rec/412.

Selle, Charles. “133 years of growth: From prairie land to bustling urban village.” Independent-Register (Libertyville), August 1, 1968.

Selle, Charles. “Settlers held services in their homes before real sanctuaries were constructed.” Independent-Register (Libertyville), August 1, 1968, p. 19.

United States of America. Illinois State Archives. Illinois Secretary of State. By Tiffani Baum and Mike Mike Standley. April 15, 2009. Accessed February 28, 2017. http://www.ilsos.gov/isa/landSalesSearch.do?purchaseNo=0048256.

Wm. Rockefeller. February 18, 1910. Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. In Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Accessed March 6, 2016. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2004003855/.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History