Going into this post, I went back-and-forth about what to write about: should I do something about Marlon Brando, who lived in Libertyville from 1937-1941? No, I thought, I should hold off on that until Oscar season. What about something about the Masonic Lodge? Well, their 150th anniversary is coming up, but I think I’ll wait until it gets closer. Looking for inspiration, I began flipping through our folders on buildings in Libertyville where I found the perfect subject for my next post: St. Sava Serbian Orthodox School of Theology! As it turns out, we have a lot of information about this unique bit of Yugoslav (now Slovenia, Macedonia, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Croatia, and Bosnia) culture in Libertyville but we had never done a post about it. Well, let’s correct that omission, shall we?

The beginnings of St. Sava can be traced to 1921, when a recent arrival from Russia, a Serbian Bishop (now Saint) named Nickolai Velimirovich started a parish in the area. Nickolai’s assistant, Archimadndrite Mardarije (born Ivan Uskokovic and declared a saint on September 15, 2015), a poor priest from Montenegro who did not own a car, walked from house to house across the Midwest collecting money, often not more than pennies, to fund the construction of a monastery. His hard work paid off, when in July 1923 he bought 33 acres just north of Libertyville, including a farmhouse which would become a priory, for $15,000. Construction of the church began in 1925 but ground to a halt in 1927 due to lack of funds. The monastery would not be fully completed for another 50 years.

St. Sava, although mainly used for the theological education of future priests, does include a beautiful, if tiny, church. The style of the church is Byzantine, marked by heavily carved doors and arches. The art that adorns the walls is more realistic than the Eastern iconography that is most often seen in churches of the Orthodox faith. The gables, located on the east and west sides of the church, house the altar and entrance respectively. The altar itself was gifted to the church by King Peter I of Yugoslavia in 1926, and has elements dating to the 15th century. The roof is made of copper sheets, which have since been weathered to a rich green patina, and sports 13 onion dome spires symbolizing Jesus and the twelve apostles. After the end of World War II, with the help of mostly non-Slavic American airmen, a monument of Dragoljub Mihailović, a partisan who fought Nazi occupation of Yugoslavia, was added to the monastery’s grounds.

The monastery became the focal point for many refugees during World War II, many of whom settled in Elgin, Kenosha, and Chicago. Among these refugees was Peter II of Yugoslavia who, having fled with his wife into exile in 1941, found himself once more without a throne when he was deposed by Yugoslavia’s Constituent Assembly in 1945. During the years after the war, he and his wife lived in a number of different places, including England, Paris, New York, and Monte Carlo.

In the early 1960s, Bishop Dionisije Milovjevich of St. Sava petitioned the patriarch (the head of the Serbian Orthodox Church) to assess his status as the sole person responsible for the Serbian church on the continent. The patriarch sent three representatives to talk to the Bishop’s congregants to judge his suitability for the position. What they heard however, were numerous complaints about misappropriations of church funds and neglect by the local administrators. Bishop Milovjevich refused to answer questions about the complaints and in 1964, the patriarch suspended him. In retaliation for his ouster, Milovjevich sued St. Sava, claiming that the charges against him were communist-inspired fabrications meant to undermine him after his criticism of Yugoslav’s President Tito. This led to a schism between the Serbian and North American branches of the church, resulting in two new churches: Free Serbian Orthodox Church and the Diocese of New Gracanica.

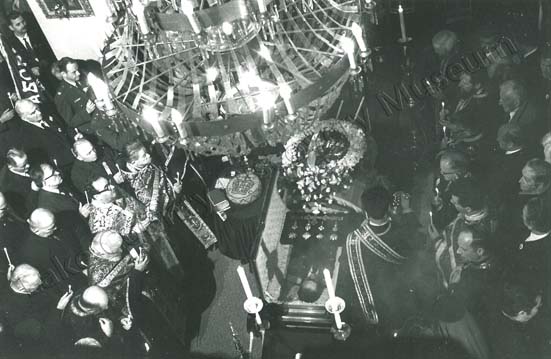

In 1970, even as the case was winding its way through the courts, Peter II of Yugoslavia, having never abdicated the throne, passed away in Denver, Colorado following a failed liver transplant. More than 10,000 people attended the funeral service as Peter II was interred at St. Sava, becoming the only European monarch to be buried on American soil.

The court case however, dragged on and by 1976 made its way to the United States Supreme Court. After ruling in favor of the Serbian Orthodox Diocese, the court handed the case back to the Illinois Supreme Court for final arbitration. Finally, after a bitterly fought and often acrimonious 14 year-long legal battle, numerous appeals, and the death of Bishop Milovjevich on May 15, 1979, the breakaway Libertyville group officially handed over the land to the Serbian Orthodox Diocese of America and Canada. Later that year, the church was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

On January 22, 2013, 43 years after being buried on the grounds of St. Sava and with the cold war over, the remains of Peter II were returned to Belgrade, Serbia where he was buried in the royal family mausoleum at St George’s Church along with his wife, Queen Alexandra, his mother, Queen Marie, and his younger brother, Prince Andrej.

Today, St. Sava continues to provide a four-year theological education to men and women, and as of 2006 had some 23 students. The church itself still provides both morning and evening mass, as well as various activities for its parishioners including pilgrimages to various orthodox holy sites in Alaska and youth summer camps. So if you’re an architectural history buff or just enjoy a beautiful building and you happen to be driving on N. Milwaukee Ave., make sure to keep an eye out for this neat little bit of Serbia nestled in the middle of the U.S.!

“Bishop Mardarije, Archimandrite Sebastian to Be Canonized September 5.” Orthodox Church in America. September 1, 2015. Accessed September 13, 2016. https://oca.org/news/headline-news/bishop-mardarije-archimandrite-sebastian-to-be-canonized-september-5.

Cox, John K. The History of Serbia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

“Expect Serbian Notables Here for Dedication.” Independent Register (Libertyville), September 3, 1931.

Garrett, William. St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Monastery Church. February 8, 2008. Libertyville. In St. Sava’s Serbian Orthodox Seminary. June 27, 2008. Accessed September 13, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Sava’s_Serbian_Orthodox_Seminary#/media/File:St._Sava_Serbian_Orthodox_Monastery_Church.jpg.

“Historical Day for Serbian People.” Serbian Orthodox Church. January 23, 2013. Accessed September 13, 2016. http://www.spc.rs/eng/historical_day_serbian_people.

Images of St. Sava courtesy of Julia Wickes

Lane, Arlene, and Schoenfield, Sonia. “A European Monarch Is Buried in Libertyville.” Libertyville Review, April 17, 2012.

Lewis, Rick. Service Honors King. November 19, 1970. Libertyville. In King Peter II Returns to Yugoslavia. March 29, 2013. Accessed September 9, 2016. http://lakecountyhistory.blogspot.com/2013/03/king-peter-ii-returns-to-yugoslavia.html.

Moser, Whet. “The Sad Life of Peter II, and the Curious Disinterring of the King of Yugoslavia From Libertyville.” Chicago Magazine, January 24, 2013. Accessed August 29, 2016. http://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/The-312/January-2013/The-Odd-Life-and-Curious-Burial-Place-of-King-Peter-II-Yugoslavias-Deposed-Monarch/

Rechner, Bernadine M. “A Bit of Serbia in Illinois.” Illinois Magazine, May/June 1984, 13-16.

Silvestri, Scott. “Monastery a Touch of Russia Close to Home.” Daily Herald (Libertyville), August 12, 1998, sec. 1.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History