Writing a post about the Native American peoples who originally lived in the vicinity of Libertyville is something I’ve been meaning to do for a while, but kept putting off. This was in large part due to the fact that, unlike other topics I’ve posted about, there aren’t many written records I can use for this post. However, after doing some exhaustive research, up to and including dropping in at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston, I feel I now have enough to cover the many tribes who used to call Lake County their home.

The earliest evidence of people living in what would become Lake County date to around 10,000 BCE, what archaeologists refer to as the Archaic period (c. 10,000-3,000 BCE). As the mile-thick glaciers that once covered much of Illinois began to recede, Native American settlers began moving northward, discovering diverse ecosystems ranging from wetlands, savanna, and woodland. We don’t know what these earliest inhabitants of Lake County called themselves, but we do know they were nomadic. They lived mainly along the Des Plaines River or Lake Michigan in birch longhouses, supporting themselves by hunting bison or mammoths using a spear thrower called an ankule, fishing, and gathering nuts and berries. Their lives must have been difficult because from what few remains have been discovered, their average lifespan was only 25 to 30 years. Archeologists gained new insights into how these earliest residents of Lake County lived when, during the construction of Wallace Road in Lake Forest in 1991, thousands of objects ranging from cooking hearths to pottery where discovered.

Approximately 200 BCE, the tribes living in the Lake County area encountered the Hopewell Culture. Rather than a single tribe or civilization, the Hopewell Culture was made up of related populations living in large, urban settlements with high levels of social stratification and practicing intensive agriculture, all traits corresponding to what archaeologists refer to as the Woodland period (c. 600 BCE-800 CE). Connected by elaborate trade routes called the Hopewell exchange, stretching from Florida to Lake Ontario in Canada, they imported a number of rare goods like fresh water pearls, mica, and jewelry made from copper or silver. They also constructed elaborate earthen mounds to serve as burial sites for their chiefs, who were buried with trade goods from neighboring tribes, often including pottery in the Havana-style, which seems to have spread from a preceding culture, reaching Illinois around 150 BCE. Then, starting around 400 CE, Hopewell exchange and the civilization it supported began to decline, finally collapsing around 500 CE. There are a number of hypothesis about what caused the collapse, ranging from societal stresses caused by the transition away from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to over-hunting due to new technologies like the bow arrow, but whatever the cause, no new mounds would be built in Illinois for the next two hundred years.

Towards the end of the Woodland period in 796 CE on the island of Michilimackinac (today known as Mackinac Island in Lake Huron), three tribes came together to form the Niswi-mishkodewin or the Council of Three Fires. These tribes were the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Neshnabé (better known as the Potawatomi), all of whom were descendants of a single tribe, the Anishinaabe, which roughly translated means “the good humans”. According to their oral traditions and Wiigwaasabak, birch bark scrolls, the Anishinaabe had originally lived near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in what is now Quebec. There, they had been visited by seven “radiant beings” who warned them to move west to escape the arrival of pale-skinned settlers. Over the next five hundred years the tribe moved west, island hopping across the Great Lakes, in a journey that would later be symbolized by a series of Turtles, with each representing an island they had stopped along the way. The most important island they stopped at was Moningwaunakauning (better known today as Madeline Island in Lake Superior), which modern Ojibwe consider the spiritual center of their tribe. According to their oral traditions, it was on that island that the Anishinaabe, after a disagreement over where to go next, split into what would become the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Neshnabé, who would eventually settle in what would become Michigan and northern Wisconsin.

Around 800 CE, construction of new earthen mounds began again marking the beginning of the Mississippian period (c. 900-1450 CE). The people this period is named after never developed a writing system, so their name, the Mississippian culture (their civilization started in the Mississippi River Valley), is unfortunately a placeholder. Among the many groups that made up Mississippian culture were the Oneota, who lived in Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. In many ways a continuation of the preceding Hopewell culture (i.e. living in urban settlements, widespread trade networks, etc.), the Mississippian culture set itself apart by building mounds with flat tops on which temples and houses for important individuals or families could be constructed. They also mined small amounts of copper, using it to make tools such as arrowheads or jewelry, which could range from something as simple as a ring to elaborate ceremonial breastplates made by riveting sheets of copper together. Their main food crop was an improved strain of maize (corn), enabling them to create larger urban settlements than the Hopewell.

Among the 2,379 Mississippian sites so far discovered in Illinois, the largest and most influential was Cahokia, located in what is now St. Clair County in southern Illinois. Built around 1050 CE, the city was massive, covering 6 square miles with neighborhoods clustered around some 190 large earthen mounds. At the city’s center, surrounded by a 20-foot tall log stockade, stood Monks Mound, which has a base larger than the pyramids at Giza and stood over 100 feet tall. At its height during the 13th century, the city was home to around 25,000 to 50,000 people, making it larger than London was at the time! Surrounding the city would have been vast fields producing the large amounts of maize needed to feed the city’s many artisans, priests, and traders. The golden age of the Mississippian culture was a short one however, and by 1400 CE Cahokia was abandoned. There is still debate over what caused this decline, although there is some archaeological evidence pointing towards increased warfare and political turmoil. Regardless, by the time European settlers arrived, all that was left were mound complexes built on such a grand scale that the white settlers, unable to accept that Native Americans had been able to build such monuments, ascribed them to the Toltecs, Vikings, and even Hindu missionaries, everyone but the people who had actually constructed them.

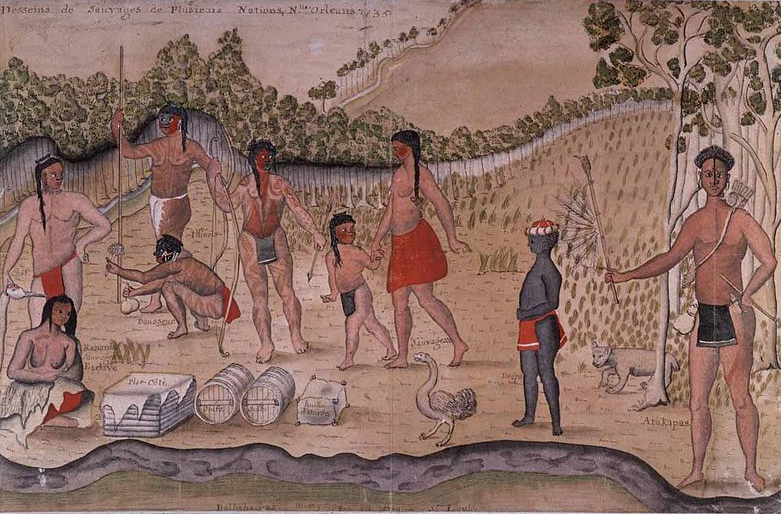

By the early 1600’s, the most powerful tribe in Illinois was the Inoca, better known to us as the Illinois, from which our state derives its name. The Inoca, whose name roughly translates to “s/he speaks normally”, were part of a loose confederation including the Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Peoria, Tamaroa, Moingwena, Michigamea, Chepoussa, Chinkoa, Coiracoentanon, Espeminkia, Maroa, and Tapouara. Semi-sedentary, the 60,000 to 80,000 members of the confederation (most of whom spoke some dialect of the Miami-Illinois language) lived seasonally in longhouses and wigwams, making their living by hunting and gathering, in addition to cultivating crops known as the “Three Sisters”, maize, beans (legumes), and squash. Men of the tribe often shaved their heads, leaving only a lock of hair, while women painted a red line down the center of their heads. Tattoos, including painting the entire body a single color, were also common. While life must have been difficult, one can imagine there must have been some nights when members of the various tribes could just sit back by a campfire, telling stories and playing games with Plum-stone dice.

Unfortunately, the arrival of European explorers would change everything. However, we’re still only up to the mid-1600’s and have a lot to cover! Join me again next time as I cover the arrival of French explorers and missionaries in the 1640’s, the impact of the European fur trade and the Beaver Wars (1628-1701), and the fight by the Native American peoples to maintain ownership of their land and preserve their way of life.

“Archaic.” Museum Link Illinois. Accessed January 25, 2018. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/pre/htmls/paleo.html.

“Cahokia mounds timeline.” Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Accessed February 6, 2018. https://cahokiamounds.org/explore/.

De Batz, Alexandre. Desseins De Sauvages De Plusieurs Nations, Nue Orleans, 1735. 1735. In Wikimedia Commons. February 15, 2008. Accessed march 16, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: De_batz.jpg.

Engberg, Tom. Copper breastplate. Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Chillicothe, OH. Accessed March 14, 2018. https://ridb.recreation.gov/images/81409.jpg.

Deuel, Thorne. American Indian ways of life. Springfield, IL: State of Illinois, 1968.

Hickerson, Harold. The Chippewa and Their Neighbors: A Study in Ethnohistory. United States of America: Waveland Press Inc., 1988.

“Hopewell Culture.” Ohio History Central. Accessed February 26, 2018. http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Hopewell_Culture.

Illiniwek ishi napungiaki connections: Lesson guides for Illinois learning standards (2nd ed.) Mascoutah, IL: Nipwaantiikaani., 1998.

Imagining the Ice Age. In Bering Land Bridge. April 14, 2015. Accessed March 21, 2018. https://www.nps.gov/bela/learn/nature/the-ice-age.htm.

Johnson, Michael G. Ojibwa: People of Forests and Prairies. Buffalo , NY: Firefly Books, 2016.

“Late Prehistoric.” Museum Link Illinois. Accessed January 26, 2018. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/pre/htmls/late_pre.html.

“Mississippian.” Museum Link Illinois. Accessed January 25, 2018. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/pre/htmls/miss.html.

Peacock , Thomas , and Marlene Wisuri. Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions. Afton Historical Society Press, 2001.

“Plum-stone dice.” MuseumLink Illinois. Accessed March 9, 2018. http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/soc_plum.html.

Temple, Wayne C. Indian Villages of the Illinois Country historic tribes. Vol. 2. Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers. Springfield, IL: State of Illinois, 1966.

“Timeline.” Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions. 2002. Accessed March 14, 2018. http://www.ojibwe.org/home/about_anish_timeline.html.

Townsend, Lloyd K. Central Cahokia. In Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Accessed March 21, 2018. https://cahokiamounds.org/explore/.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History