The Winchester House, soon to be moved to Mundelein, might today be the place you go to visit your grandparents, but did you know that the nursing home is the descendant of the Lake County Poor Farm? For almost a century, through scandals, economic depressions, and a number of name changes, the poor farm stood as a place of last resort for residents of Lake County with nowhere else to go.

The origins of the Lake County Poor Farm can be traced to the first industrial revolution. Starting around 1760 and lasting until the early 1840’s, this period saw a dramatic rise in the number of people living in abject poverty, caused in part by the unreliability of factory jobs along with a number of financial panics. One of the ways society dealt with the problem was the creation of poor farms, sometimes called almshouses or workhouses. Poor farms were places where the “deserving” poor (poverty being seen at the time as a moral failing) were expected to work to pay for their upkeep and keep them from their perceived innate idleness, and in this Lake County was no exception.

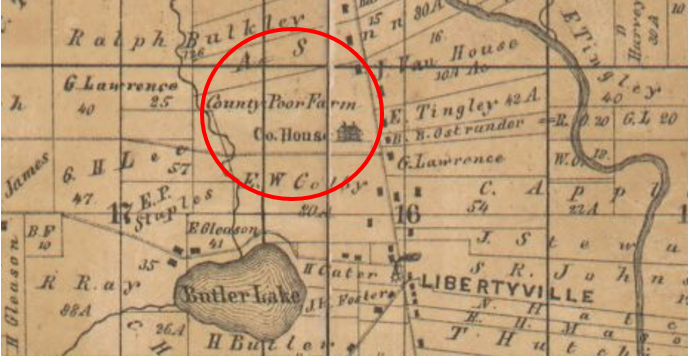

At a special meeting of the Lake County Commissioners Court in October 1847, it was decided to purchase 190 acres of farmland from Alva Trowbridge, also a commissioner at the time, for $2,025 ($57,045 today) to be used as a poor farm. Located at what is now the Northwest corner of Milwaukee Ave. and West Winchester Road on the edge of Libertyville, the farm included a comfortable farmhouse, barn, as well as a small wooded area around 10 acres in size. However, the commissioners soon realized that their plan was more expensive than they had originally anticipated, leading the newly constituted board of supervisors to adopt a resolution on November 15, 1850 to sell the farm and send the poor away. The board’s decision led to warring editorials in local papers about the pros and cons of a poor farm along with a large number of residents protesting the sale at a crowded meeting on December 6, 1850. Because of the protests, the board rescinded their previous resolution, retaining the farmhouse along with 35 acres. The controversy over the poor farm wasn’t over yet though, with residents arguing over whether it should be paid for by Libertyville or Lake County. Eventually after much back-and-forth and two separate injunctions in the local court, the issue was put to a vote. At a meeting of Supervisors on May 11, 1853, the vote count found 636 in favor of county support to 531 for township support, clearing the way for the construction of an almshouse in 1855.

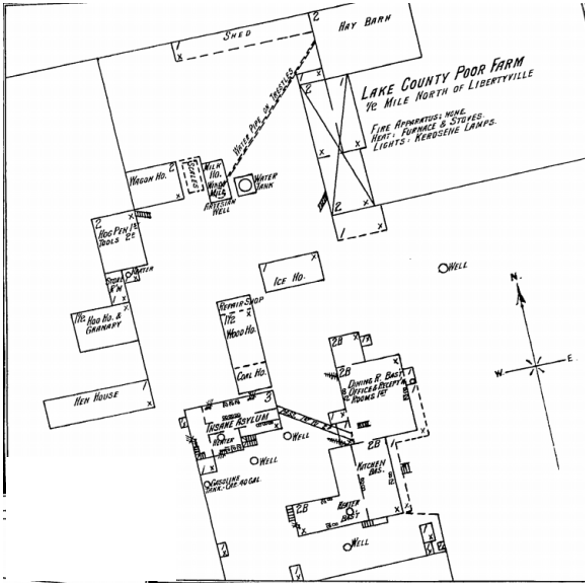

According to the newspaper accounts of the time, the poor farm offered “little more than food and shelter” for its residents, made up largely of unwed mothers, people dealing with alcoholism or mental illness, and those who simply had nowhere else to go (History). The earliest residents of the farm lived in a cramped, ill lit, two-story brick house with little to no ventilation. Men and women were kept separate, with women sleeping on the first floor, men on the second, and an enclosed porch being used to house people suffering from mental illness. Residents who weren’t bedridden were expected to work to help pay for their own upkeep, producing beef, raising chickens, and attending to the vegetable garden and orchard. In 1870, Charles Appley was elected as the first director for the poor farm. In 1883 an annex with iron bars on the doors and windows was built to house inmates dealing with mental illness (some of whom were kept locked in their rooms day and night). Another feature of the farm was a pauper’s cemetery for residents who could not afford to be buried elsewhere. I was not able to determine when it began, but an obituary for a resident of the poor farm in the Libertyville Independent dates it to at least as early as January 1918. Despite these Dickensian conditions, there were some bright spots. One came on December 25, 1905, with the Independent Register reporting on the farm’s “Unfortunate” being treated to a merry holiday party, with gifts from family and friends, and a feast of chicken, cranberry sauce, dumplings, mashed potatoes, and oysters (Lake County Independent 1905, p. 5).

By the early 1910s, there were fifty-two people living at the farm, in addition to the three women and one man the county hired to care for residents and to help tend the one hundred and fifty acre farm. On November 9, 1912, the State Charities Commission inspected the farm, and in its report, recommended the immediate removal of residents suffering from mental illness along with repairs to the almost sixty-year-old almshouse. The removal of mentally ill residents would eventually be accomplished, although not without changes in state law all but forcing the supervisor to do so.

Then, on March 16, 1918, a scandal erupted when it was revealed that a twenty-six year old resident of the farm named Lina Larsen, who was described in the papers as a “half-wit,” was pregnant (Libertyville Independent 1918, p.1). A meeting of the Board of Supervisors was held in Waukegan on March 21, where the now seventy-year-old Appley was questioned about the matter. After the meeting adjourned, a reporter from the Waukegan Daily Sun, attempting to interview a committeeman, was told only that “He admits he is guilty” (Libertyville Independent 1918, p.1). Crying, Appley begged the reporter not to put his name in the paper, saying that he would “pay any sum necessary to hush matters up,” but the damning conversation was published anyway in the next day’s edition of the paper (Libertyville Independent 1918, p.1). Charles Appley resigned on Friday, April 19, and on Thursday, April 25 his son, Schuyler Appley, was appointed superintendent of the farm.

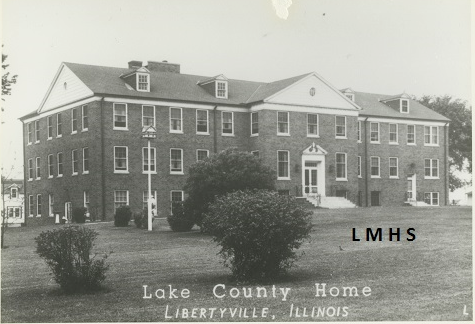

Schuyler Appley passed away on November 20, 1920 and was replaced by Philo J. Burgess of Mundelein, who was appointed Superintendent on December 27 with a salary of $1,000. Burgess was soon joined by his wife Aura, who became the assistant Superintendent. They quickly made their mark on the farm, changing its name to the Lake County Home, purchasing an additional 100 acres of land, and in the words of Aura, being “on call 24 hours a day” caring for the farm’s 42 residents (Independent-Register 1976, p. 7). During the 1920’s, the Lake County Fair was held at the end of Appley Avenue, now the site of Lake Minear, where patients of the farm were given free admission. Among these was a patient named Rasmus Truax, who believed that he was a police officer, and could often be seen on the streets of Libertyville in his official-looking uniform, directing traffic and joking with passing motorists. In 1926, the seventy-year-old almshouse underwent a series of major renovations, including widened stairways, modern plumbing, and additional bed space, allowing for up to 90 residents who required medical care. The people of Libertyville took a certain amount of pride in the farm, with the County Board Chairman Martin Ringdahl declaring in 1928 that he “couldn’t find a weed” and compared the farm to those of Samuel Insull and J. Ogden Armour (Independent-Register 1976, p. 7).

Then, on October 29, 1929 the markets fell, marking the beginning of what would become known as the Great Depression. Predictably, as factories closed and bread lines grew, more and more people turned to the farm, which at one point had one hundred and twelve residents. Among the farm’s residents during this time was a man who, despite having lost his wealth in the crash, insisted on remaining impeccably dressed despite his circumstances. In 1932, the county estimated that it spent 96 ¢ per day (around $17.26 today) to feed, house, and clothe each resident of the farm. Despite the economic hardships of the depression, every fall residents could count on county officials to have a party at the farm to celebrate the beginning of Pheasant hunting season. By this time however, the public’s perception of what role local and state governments had in providing for the poor and elderly was changing.

This was in part due to the muckraking journalism of the time that exposed the conditions that residents of poor farms were living in. Another factor were the safety nets created by the federal government in the wake of the Great Depression, including Social Security, Aid to the Blind, and Aid to Dependent Child Program, all of which enabled people who would have previously been forced to live on the poor farm retain their independence. Together, these trends would lead the eventual end of the poor farm system. Rather than disappearing outright though, a number gradually transformed into nursing homes. In November 1939 the farm’s cemetery closed, reverting back to just another field. The next year in 1940, the same year residents stopped working the farm, its name was changed again to the Lake County Nursing Home. In 1973, the current five story nursing home was built at a cost of $2.5 million ($ $13,782,995 today) and renamed once again, becoming Winchester House, completing the sites transformation from poor farm to nursing home.

Today there isn’t much left of the original farm, save for a small bronze plaque honoring the residents of the farm buried in the pauper’s cemetery. Erected in 2002 by local boy scout Brian Dowd as part of his Eagle Scout project, who combed through Winchester House archives to identify what residents were buried in the cemetery. It wasn’t long after being put up however, that the marker was hidden by untrimmed trees and overgrown alfalfa. Happily, the cemetery had a bit of cleaning up in November 2014 by teen ministry volunteers from St. Joseph Catholic Church. I hope you enjoyed this post, and will join me next time when I cover the life and times of Dennis “Denny” Limberry, Libertyville’s fire marshal, deputy sheriff, Thistle commissioner, and member of the local Democratic county central committee during the late 19th and early 20th century.

“Abhorrent but necessary of discussion.” Libertyville Independent, March 21 , 1918. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3147991/data?n=1.

Alfredson, Linda. “A home for the homeless.” Independent-Register, March 25, 1976.

“Appley resigns, son succeeds him.” Libertyville Independent, March 21, 1918. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3171770/page/1.

Burgess , Aura . Humorous side of life at the Lake County Home. Typed essay, Libertyville.

Hale, George. Map of Lake County, Illinois. St. Louis: L. Gast Bro. & Co. Lith, 1861. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013593105/. (Accessed October 30, 2017.)

Halsey, John J. A history of Lake County Illinois. Philadelphia , PA: Roy S. Bates, 1912.

“Handsome home to house poor in Lake County.” Chicago Daily Tribune , May 24, 1942. Accessed October 23, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/hnpchicagotribune/docview/176710435/F718019DFCC54A3FPQ/1?accountid=44868.

Hansan, John. “The New Deal: Part II.” VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project, 2012. Accessed October 23, 2017. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/great-depression/the-new-deal-part-ii/.

History. April 1, 1974. Description of the history of the Lake County Poor Farm, Libertyville.

“Holiday joy for unfortunate.” Lake County Independent (Libertyville), December 29 , 1905. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3169841/page/5.

Krishnamurthy, Madhu. “Their place in history.” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights), July 5, 2002, sec. 5.

“Libertyville Lake Co. ILL.” Sanborn-Perris Map Co., 1897. Accessed October 26, 2017. http://sanborn.umi.com/il/1973/dateid-000001.htm?CCSI=277n.

“May move insane from the Poor Farm.” Lake County Independent (Libertyville), December 20, 1912. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3170113/page/9.

Mink, Gwendolyn and Alice O’Connor. Poverty in The United States: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, and Policy. Vol. 1. 2 vols. ABC-CLIO, 2004.

“Once rich, dies at the County poor farm Mon.” Libertyville Independent, January 17, 1918. Microform.

Photos courtesy of the Cook Memorial Public Library District and the Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

“Says removal of bars at County Farm is now due.” Libertyville Independent, September 26 , 1918. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3171798/page/1.

“Schulyer Appley appointed.” Libertyville Independent, April 25 , 1918. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://vitacollections.ca/cmpldnewsindex/3171776/page/9.

U.S. Illinois General Assembly. General Laws of the State of Illinois. 17th Cong. Doc. Springfield , IL: Lanphier & Walker, Printers, 1851. 52. Accessed October 9, 2017. https://archive.org/stream/lawsofstateofillin17illi#page/52/mode/2up/search/poor.

Waller, C. L. “For 150 years, Lake County site has helped others.” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights), April 17, 1997.

Watson, Sidney D. “From Almshouses to Nursing Homes and Community Care: Lessons from Medicaid’s History.” Georgia State University Law Review: Vol. 26 : Iss. 3 , Article 13. Accessed October 9, 2017. http://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss3/13.

Williamson, Conner. Cemetery Record: Lake County Poor Farm Libertyville, Illinois 1923-1939. 2002. Eagle Scout Project , Libertyville.

Wilson, Marie. “‘Sad’ cemetery gets spruce-up from Libertyville teen ministry volunteers.” Daily Herald, November 1, 2014. Accessed October 25, 2017. http://www.dailyherald.com/article/20141031/news/1410039479.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History