In our last Ansel B. Cook post, we learned about Ansel B. Cook’s youth in Haddam, CT, his training as a stone mason, and the family’s move to Illinois in 1846. In today’s post, we’ll look at Ansel’s success in Chicago’s business and political worlds.

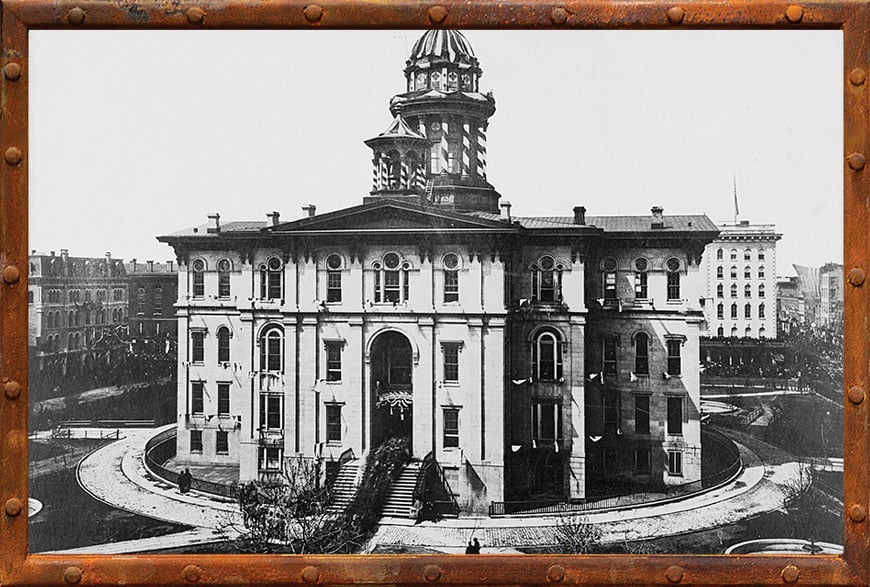

In 1853, Ansel and Willard Cook (Ansel’s father) secured the contract to lay the stone sidewalks around the Cook County courthouse (seen below) to be constructed on the block bounded by LaSalle, Washington, Clark, and Randolph Streets. With this coup, the Cooks moved to Chicago where they operated a stone yard on the corner of Market and Quincy Streets, which today is home to the Willis Tower.

In 1862, Ansel was nominated by the Builders’ and Traders’ Association of Chicago as the Republication candidate for the Illinois state legislature. He would run to represent District 59 which included the west side of Chicago and nine “country towns.” Ansel won the seat and took office in 1863.

While serving, Ansel unearthed a conflict of interest involving the State Commissioner, the Speaker of the House, a state senator, and the Chairman of the Penitentiary Committee. He discovered that the provisions of the state constitution were being violated in the matter of letting contracts for prison labor. The four gentleman each had a 1/4 interest in the contract. Ansel’s “investigation and vigorous opposition resulted in the abrogation of the contracts and placing of the prisoners under direct control of the state.” (Portrait and Biographical Album of Lake County, Illinois). Having gained a reputation for honesty and reform-mindedness, Ansel was elected to a second term in 1865. After serving this second term, Ansel “removed to Libertyville” due to “bad health.” (Libertyville Illustrated). His wife Helen, and daughter Ida F. Cook, whom Ansel and Helen had adopted sometime around 1857, accompanied him.

Whatever the bad health was, Ansel did not slow down. While residing in Libertyville, Ansel was elected and served as Libertyville Township Supervisor in 1867 and state representative from Lake County in 1868. His Chicago masonry business continued to prosper. In 1869 he won the masonry contract for the historic Chicago Water Tower designed by architect William W. Boyington.

In Libertyville, Ansel and family most likely resided in the home of his father-in-law, Dr. Jesse H. Foster, which stood on the site of the current Ansel B. Cook Home. The 1870 census shows a full household with Ansel, Helen, Dr. Foster, Lizzie Foster Demming (Helen’s sister), Helen A. Demming (age 1, Lizzie’s daughter), and two servants in residence. Ida Cook was away at school at Lake Geneva Seminary from which she graduated with honors in 1874. In the 1873 Bird’s-Eye View of Libertyville shown below, one can see a residence in the center, sitting back from Milwaukee Avenue.

When the current Ansel B. Cook Home was built in the late 1870s, Dr. Foster’s house was moved to what is today Cook Avenue [Cook Avenue going west did not exist until 1897] and was used as a caretaker’s house. The house stood at 132 W. Cook until the mid to late-1960s.

After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Ansel returned to Chicago to help rebuild the city in partnership with William Price, another builder with Libertyville ties. Over the next several years the partnership built several business blocks including the American Express building (21-29 W. Monroe Street, built 1872, demolished 1919) and the Bryant Block (NE corner of Dearborn and Randolph, built 1872). The Bryant Block is now known as the Delaware Building and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Back in the thick of things in Chicago, Ansel again entered the political arena. From 1877-1879, he served as alderman from the 11th Ward – an area bounded approximately by the Chicago River on the east, Carpenter St. on the west, Ohio St. on the north, and Randolph St. on the south. During his tenure he served as President of the Council and served on the judiciary, local assessments, public buildings, wharfing privileges, harbor and bridges, and public buildings committees.

As chairman of the building committee responsible for erecting a new city hall, Ansel weighed in on the selection of the stone for the building. The structure was to be built on land owned by Cook County and immediately next to a new county courthouse to be built at the same time. The County and the City agreed to build the new city hall and the new county courthouse alike in appearance. However, Ansel did not approve of the Lemont stone preferred by the County. He recommended Bedford stone which was similar in color but more durable.

In a speech before the City Council, Ansel predicted that in less than 10 years the Lemont stone would begin to “spall” [chip] off and that a new building would be required within 50 years. The County stayed with the Lemont stone and the City built with Bedford stone. After many delays, the County section was completed in 1882 and City Hall in 1885. Six years after the completion of the county courthouse, the Lemont stone did indeed spall and $150,000 [over $3 million in 2016 dollars] was required to cut down the cornices and take other safety measures. The City Hall, which was of the same size, same architectural design and half the cost, was fine, proving Ansel right.

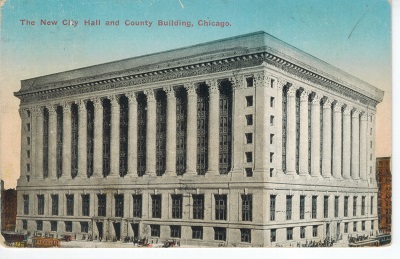

However, by the time City Hall and County buildings were complete, they were already out of date, overcrowded, and poorly suited to the use. In addition, the experimental mat-and-pile foundation system that was used failed. In 1905, the building’s foundation sank six inches. A ruptured gas-pipe led to an explosion which blew the roof off the building. Plans began for another new set of buildings. The resulting structure still stands today on the city block bounded by Randolph, LaSalle, Washington, and Clark streets.

During this time, Cook’s influence, status, and pocketbook grew. About 1876 he began work on a fine new country house to reflect his stature in the business and political world. The work was completed about 1878. The architect is thought to be William W. Boyington with whom Ansel worked on the Chicago Water Tower project. Mr. Boyington also designed the Union Church of Libertyville (1868), which sat where St. Lawrence Church is today, and the Libertyville Town Hall (1894), today’s American Legion hall.

While the 1870s were a high point in the life of Ansel B. Cook, the 1880s and 1890s would prove to have ups and downs, particularly in his personal life. Our next blog post in this series will take a closer look at the significant events over the last 20 years of his life.

Sources:

- “Willard Cook.” In Currey, Josiah Seymour, ed. Chicago: It’s History and It’s Builders (p. 522-527). Chicago, Illinois: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1918.

- “Hon. Ansel B. Cook.” In Portrait and Biographical Album of Lake County, Illinois (p. 457-459). Chicago, Illinois: Lake City Publishing Co., 1891.

- Liberyville Illustrated, 1897, p. 14.

- No. 6.692, p.3, Abstract of Title, Lake County Title and Trust Co., Waukegan, IL at Lake County Geneological Society, Folder 1.

- Chicago’s Seven City Halls. WTTW. http://interactive.wttw.com/timemachine/chicago%E2%80%99s-seven-city-halls. Accessed 10-27-2016.

- Chicago City Directory and Business Advertiser, 1855-56. p.112.

- U.S. Federal Cenus, Libertyville Township, Lake County, Illinois, 1870.

- U.S. Federal Census, Geneva Village, Wisconsin, 1870.

- Carroll, C.E. “History of Libertyville” Unpublished manuscript. Libertyville-Mundelein Historical Society.

- Libertyville Telephone Books, 1951-1959, 1961, 1965, 1967, 1969, 1972

- “William Price.” In Andreas, A.T., ed. History of Chicago from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Volume 3 (p. 89). Chicago, Illinois: The A.T. Andreas Company, 1886.

- American Express Building. https://chicagology.com/rebuilding/rebuilding043/. Accessed November 14, 2016.

- Summary of Ansel B. Cook information from The Chicago City Council Proceedings. Correspondence from Sandra K. Rollheiser, Assistant Reference Librarian, Chicago Munincipal Refernce Library, February 20, 1975. In Biographies – Cook, Ansel Brainerd folder of Local History File, Cook Memorial Public Library.

- Bright, Wendy. “A History of Chicago’s City Hall and Cook County Building.” Written January 26, 2015. http://www.chicagoarchitecture.org/2015/01/26/a-history-of-the-cook-countycity-hall-building/. Accessed November 23, 2016.

- Schoenfield, Sonia. “W.W. Boyinton.” The Past is Present Blog, Cook Memorial Public Library, https://shelflife.cooklib.org/2014/01/25/w-w-boyington/. Accessed December 7, 2016.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History