Everyone thinks of World War II as the time when the whole country came together and sacrificed to win the war. Believe it or not, World War I had a few “come together and support the war effort” movements, as well. One of them, the Woman’s Land Army of America, took place in our own backyard.

Everyone thinks of World War II as the time when the whole country came together and sacrificed to win the war. Believe it or not, World War I had a few “come together and support the war effort” movements, as well. One of them, the Woman’s Land Army of America, took place in our own backyard.

The Woman’s Land Army of America was modeled after the Women’s Land Army in England, where city girls went to the country to help on the farms while the farmers were away fighting the war. Since the First World War lasted much longer for England than it did for the United States. their program had a chance to become established. With the United States’ late entrance into the war, our country’s farms were not as severely affected as the British farms were. Nevertheless, the Woman’s Land Army of America played an optimistic and enthusiastic role in women’s war work in this country, setting the stage for future movements.

The WLAA took root in the eastern and western states in 1917 and was generally associated with colleges and universities. Here in the Midwest, Chicago specifically, society activist women like Mrs. Margaret Blake took on the organization and adapted the coastal WLAA to fit our needs. Specifically, the farms were not used just to provide food or to “hold the fort” while the men were at war. The project was also meant to be a training ground to bring women into agriculture, whether as farm owners, workers, or wives.

In February of 1918 Mrs. Blake and other like-minded women of Chicago attended a suffrage meeting in Washington, D. C. where they all pledged women’s support of the war. This included setting up training farms for women.

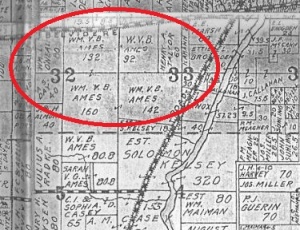

By March the Illinois branch of the WLA had been formed. After hearing Miss Helen Fraser speak about the Woman’s Land Army in Britain, W. V. B. Ames, the husband of one of Mrs. Blake’s committee members, donated his 200-acre Warren Township farm to the cause for three years. This property is now owned by the Merit Club south of Belvedere Road, Highway 120.

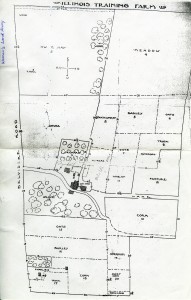

Once they had a farm, the Illinois WLAA gained momentum. They started recruiting women, or “farmerettes” as they came to be called, to work on the farms. Since there was no government funding for the program, the Chicago committee women solicited donations large and small from corporations and retailers, acquiring everything from tractors and livestock to kitchen utensils and canning jars. By the end of April the Illinois Training Farm was up and running. Its purpose was to train women for farm work who could then train other farmerettes, and so on. The term farmerettes was originally meant as a derogatory term, similar to the suffragettes who worked for women’s right to vote. In time the term became used with more respect.

The Ames farm, when the WLAA took ownership, was a little run down but in no time at all the women had it in working order. Miss Blanche A. Corwin, a graduate of Cornell Agricultural College with experience in teaching and farm management, supervised the day-to-day activities. Up to 40 women lived on the farm, carrying out all the duties a farm of that size required. The farmerettes milked cows, raised chickens, plowed fields, and tended vegetable gardens, thus gaining a diverse education on a real working farm. Throughout the summer the farmerettes toiled diligently on the training farm, and in the fall they reaped more than one harvest. Crops were brought in and a new breed of farm woman had been born.

The young women thrived on the farm, taking pride in their hard work. “Think of it,” cried farmerette Adaline, “I’m milking five cows every day now. When I came I was afraid of a cow.” Another farmerette who had left her job as a telephone girl declared, “How did I ever endure it? Why I hate even to think of going into Chicago for a visit now. Seems as if I could never breathe cooped up again.” (Independent Register, May 23, 1918., p. 4)

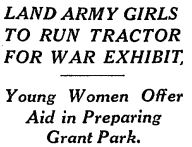

The Libertyville farmerettes made a name for themselves when they pitched in to help prepare for the War exposition planned for Grant Park in Chicago that fall. Six young women traveled to Chicago, with their tractor, to level the park’s grounds for the exhibits and programs. Apparently young women on tractors were just as much a spectacle as the exposition.

The biggest event in the life of the Illinois Training Farm was graduation day, September 17, 1918. Governor Lowden was invited and, being a country boy himself, he sat down and milked a cow after giving his speech and presenting the graduates with their brassards to certify their completion. The training farm experiment was deemed a complete success by all involved and the future looked bright. The 1918 annual report of the Illinois Training Farm cataloged the farmerettes’ activities: “The women have plowed with horses and tractor; planted, cultivated, made hay, gathered crops, filled silos, raised horses and cows, drained land and helped construct buildings. They have raised chickens, tended bees and done dairy work, including butter and cheese making. In May they set out about 2,000 tomato and 5,000 cabbage plants; seeded 70 acres of hay, 3 acres of alfalfa, 22 acres of corn, 11 acres of oats, 7 acres of barley, 2 acres of wheat, 3 acres of sweet corn and 4 acres of potatoes.” (Illinois Training Farm for Women, 1918).

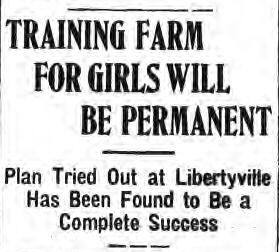

The future looked bright for the training farm at Libertyville. The newspaper touted its success and laid out plans for the future: “From now on the farm will be chiefly a dairy farm–the particular work for which women have been found to have the greatest aptitude–with departments of poultry raising, animal husbandry, bee-keeping, general crops, vegetable gardening and home economics.”

But then came the event that closed down the farm: the end of the war.

On November 11, 1918, the Armistice of Compiegne was signed and the war came to a close. All of a sudden the main impetus for the farm had vanished, and even though the Illinois Training Farm had had an educational vision beyond supporting the home front food supply, backing for the endeavor was no longer there. According to newspaper reports, the farm was unable to find the funding it needed to keep running. Eventually the entire operation was turned over to Blackburn College in Carlinville, Illinois. Farming equipment as well as livestock were sent to the southern Illinois college, leaving a few buildings, memories, and a number of skilled young farmerettes. “The discovery at the Libertyville farm of the country by the city born girls who forsook offices and colleges to study practical farm work, was delightful to watch. Enthusiastic, clever, quick, and untiringly diligent, almost to a girl they made good. Not one of them returned to city life without a larger vision of the desirable possibilities of out of door, country existence.” (Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1920, p. F4) The Illinois Training Farm of Libertyville proved to the world that women could successfully farm, and proved to the women that such work was fulfilling, noble and a worthy result of a single year’s farm output.

Today all that is left of the Illinois Training Farm is a barn and the memories of local efforts to support the war, supply food for the community, and provide and agricultural education to interested and enthusiastic young women.

Sources used:

Calhoun, Lucy. “Women in Wartime.” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 6, 1918. p. 11.

Calhoun, Lucy. “”Women in Wartime.” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 13, 1918, p. 12.

“Day is Full and Life Happy for Farmerettes.” Libertyville Independent, May 23, 1918, p. 4.

“Enlists Women for Land Army Near Libertyville.” Libertyville Independent, April 11, 1918, p. 1.

“Failure to Get $20,000 Closed Libertyville Farm.” Libertyville Independent, March 6, 1918, sec. 2, p 1.

“Farmettes in First Laps of Real Farming.” Libertyville Independent, April 25, 1918, p. 1.

“Governor Sees Army of Women Labor on Farm.” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 18, 1918. p. 3.

Illinois Training Farm for Women of the Woman’s Land Army of America, Inc., 1918.

“Land Army Girls to Run Tractor for War Exhibit.” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 28, 1918, p., 3.

“Liberty Farms Training Women for Land Army.” Libertyville Independent, May 30, 1918, p. 1.

“Libertyville’s Farm Idea Spreads to Other Places.” Libertyville Independent, October 10, 1918, sec. 2, p. 1.

“News of Chicago Society.” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 16, 1920, p. 14.

“News of the Chicago Women’s Clubs.” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 17, 1918, p. C5.

Schultz, Rima Lunin, and hast, Adele. “Blake, Margaret Day,” in Women Building Chicago, 1790-1990. A Biographical Dictionary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001.

“‘That Farm is in Our Town,’ Insist Warren Farmers.” Libertyville Independent, October 24, 1918, p. 1.

“They Are Looking for Healthy Women for Farm.” Libertyville Independent, May 16, 1918, p. 2.

“Training Farm for Girls Will Be Permanent.” Libertyville Independent, October 17, 1918, sec. 2, p. 1.

“War Relief and Its Agents Now Finishing Job.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 1, 1919, p. 14.

Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory, Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2008.

“Women to Learn Farming on Place Near Libertyville.” Libertyville Independent, April 4, 1918, p 2.

“Women’s Farm Moves Away.” Libertyville Independent, February 27, 1919, sec. 2, p. 3.

Categories: Local History

Tags: Local History